Written by Harriet Maher

March 24, 2022

A review of the memoir by Ai Weiwei

Ai Weiwei with porcelain sunflower seeds, from the 2010 installation at Tate Modern

We often rely too much on our understanding of an artist’s identity, their life story, in order to glean meaning from their work. But it can be distracting and even misleading to pin our interpretation of an artwork on the fact that the artist is from a particular cultural background, of a certain age or gender, or worked in a specific style or movement. Not only does this framework position the artist at the epicentre of meaning-making and removes our own autonomy in determining significance. It narrows our view of how art can impart meaning across different cultures, experiences, and historical periods.

However, in the case of Ai Weiwei, there is something to be said for a deeper insight into his personal life, his family history, and the geopolitical circumstances that prompted him to produce some of the most complex and thought-provoking art of the 21st century. Maybe it’s because his art has always mirrored, or rather exposed, the real world we live in, the tragedies and atrocities that occur on our planet at an alarming rate. His art is inseparable from his life, because his life – his tweets, blog posts, personal experiences and even his Instagram feed – has become a significant facet of his art.

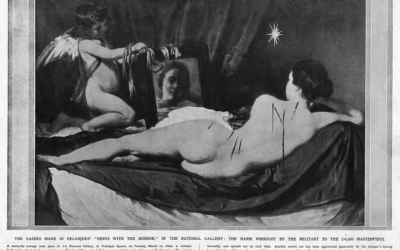

His memoir, 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows, spans much more than his own life as a relentless thorn in the Chinese government’s side and a revered favourite of the Western art world. It traces his lineage back to his father, the poet and writer Ai Qing, who was exiled for much of his life in the harsh Chinese wilderness because of his reputation as a ‘rightist’, and for his open criticism of the Chinese Community Party. Ai Weiwei spent a significant portion of his childhood in one of the labour camps his father was sent to, and he recalls how this experience helped him to “think of art as a beginning: it is when we push ahead, regardless of the consequences, that we give meaning to our lives.”

Ai Weiwei with Ai Qing at Tiananmen Square, Beijing, China, November 1959

The ongoing interrogation of power structures, their concealment and subsequent weaponisation against the general population is a recurring theme in Ai Weiwei’s life and work. His book tells of the myriad ways in which he and his work were censored, denigrated, and outlawed, leading to his famed incarceration for eighty-one days in 2011. It was during this period of separation from reality – from family, friends, work, and all news of the outside world – that he conceived of this book. His idea was not only to tell his own story for the sake of his son, but also his father’s story, for the sake of himself and other Chinese whose past histories and material lineages are systematically being erased. In doing so, Ai has created a searing and in-depth account of the twentieth and twenty-first century in China, using these two personal histories as an allegory of the times.

Through his art practice, Ai Weiwei has tirelessly sought to bring attention to major humanitarian issues, never shying away from things that seem too difficult to talk about – the 2008 Sichuan earthquake that killed thousands of children and was covered up by Chinese authorities; the Syrian refugee crisis; state surveillance and police brutality. Scale is something that struck me as a central tenet of Ai’s work, even through the written word. His enormous, overwhelming works at scale reveal the mind of someone who has a compelling need to expose problems facing society today. We cannot look away from Ai’s works – the one hundred million individually hand-crafted porcelain works of Sunflower Seeds; the 9000 children’s backpacks of Remembering; or 1001 Chinese nationals who he brought to Germany for his work at the Documenta show in 2017 – they are simply too big to ignore.

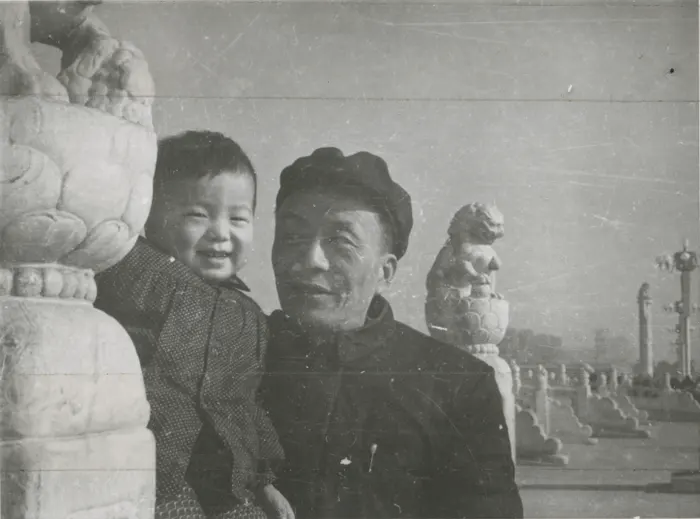

Ai Weiwei, ‘At the Museum of Modern Art, 1987’, from the New York Photographs series, 1983–1993

I remember going to see the Andy Warhol x Ai Weiwei show at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne a few years ago and thinking about how art can create a common language across geopolitics, culture and epochs. This book cultivated the same feeling in that it highlights the string through time that connects Ai Weiwei’s struggle to find and express personal freedom in the face of authoritarian regimes, with that of his father, who was brutally persecuted for doing the same. Both managed to find solace and power through art and poetry, respectively, and this book tells the story of how dangerous and how brave this endeavour can be.

I won’t say the book is an easy read; there are a lot of names, dates and places to keep track of in a century-long history of two lives interwoven with the construction of a nation. But it is an important read, and one that lifts the lid on why Ai Weiwei is one of the loudest and strongest artistic voices of our time.

Related Articles

Weekend Viewing: 13-15 January

It's a new year and there is a brand new lineup of shows opening around the world . Here are some of my top picks for exhibitions to check out this weekend, both online and in person. From biennials to blockbusters and everything in between, this short list will...

My Robot Could’ve Made That

There is a well-known book on modern art called “Why Your Five Year Old Could Not Have Done That.” It speaks to the once-common dismissals of abstract and ‘primitive’ styles of art as childish; art that we now prize above any other genre. But perhaps the next...

Just Stop.

Why using art as a vehicle for protest isn't the solution There’s been a lot of art in the news lately, but not necessarily for the right reasons. We’re used to seeing Picasso, Van Gogh and Munch’s names splashed across the pages of newspapers and the internet, but...