Written by Harriet Maher

April 28, 2021

A lot of people want their art to be serious, sharp, cold, minimalist. I like mine with a smudge of the abject: to see bodies touching, feel a jolt of desire or awakeness or recognition. This notion of intimacy seems to permeate a lot of the most popular art of our time, from the skin-infused scenes of Normal People to the wildly popular Instagram account dedicated to photos of people’s hands touching on the New York subway. Maybe it’s that it represents a universal basic human need, the need for social (and physical) interaction.

1

One of the first pieces of art I remember falling in love with was Rodin’s Cathédrale, a templed pair of hands with the fingertips barely brushing together, which, in the midst of a global pandemic, probably feels like soft porn to a lot of people. I even preferred the plaster model version to the finished bronze, because it feels more raw, more like real skin touching. I know I’m not alone, because I see it in the profound popularity of artists like Sarah Bahbah (aesthetic successor of Petra Collins), whose softly lit and richly coloured images of young, attractive people belie a sense that you’ve stepped into a private scene. It’s a room, or a world, on which the door should have been closed, but was left slightly ajar, either on purpose or by mistake. The intimacy is heightened by her searing text captions, which reveal the exact millennial dilemma of how to be intimate, how to trust; the ennui of youth, and the fear of losing interest – or of someone else losing interest in you.

2

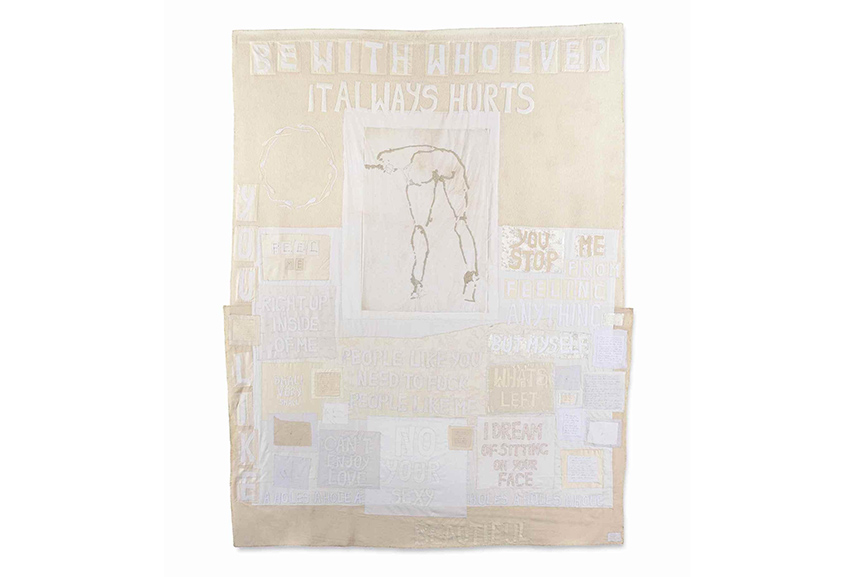

Intimacy is about loss and suffering as much as it is about joy and belonging. No one quite captures that painful dichotomy as poignantly as Tracey Emin, the harbinger of making art intimate, rather than aloof. While she is best known for her raw, gut-punching installation My Bed (1998), all of Emin’s work conveys the physical and emotional difficulties of being close to someone else. It Always Hurts pulls together threads, both physical and conceptual, of the feeling of loving someone, and loathing the power it gives them over you. It’s something everyone feels acutely aware of, standing in front of the milky cotton colours of Emin’s blanket, or even staring at it through a cold flat screen where the warmth of fabric and touch can’t reach you. The words sewn into the quilt evoke the truth of intimacy, of love – that it’s at once wonderful and devastating. The phrases “can’t enjoy love” and “you stop me from feeling anything but myself” coexist on this monochromatic surface, further enhancing the ambiguity of what we feel in front of this work, and in front of someone we feel strongly for.

3

Taking a less literal approach to intimacy in art, Felix Gonzalez-Torres uses minimalist artistic approaches to explore concepts of a more personal and meaningful nature. His works are intimate, yet often associated with the loss of intimacy. As a gay man living and working during the 1980s AIDS epidemic, Gonzalez-Torres lost his partner to the disease, and died himself from the same cause less than a year later. All of Gonzalez-Torres’s work points back to their relationship; he once said that his body of work was made for an audience of one – Ross. So why, if the work is so personal, so individually focused, does it move us so profoundly, regardless of our background, sexuality or lived experience? The answer is simple – intimacy, love, and loss are universal human experiences so basic that they are essentially woven into the fabric of our being. We may not have lost a lover to disease or death, but we can imagine the terrible pain of missing the connection to someone we imagined to be infinite. In his stunning expression of personal experience, Gonzalez-Torres opens up his own life to the public arena, and makes a political statement about something extremely intimate and private. Not only did the AIDS crisis cause immense individual suffering, it was an intensely controversial and powerful political weapon, waged against homosexual and drug-addicted communities in a manner that almost obliterated an entire portion of the population. Gonzalez-Torres highlights that without ever needing to do so explicitly. Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) hits us square between the eyes with the gravity of losing someone we love, without ever showing the face of any person, their body, or any graphic decay. The work consists of a pile of candy cascading over the floor and slowly dwindling away to nothing, as visitors are invited to take a piece of the installation with them. The weight of the pile (ideally 175lb) corresponds to Ross’s body mass when he was healthy. The methodical erasure of the work by many hands is a heartbreaking reflection of the decimation of his body by HIV/AIDS, and the eventual eradication of the body’s presence altogether. Although this work specifically relates to Ross, it also speaks more widely to the steady, sustained depletion of the gay population of the world in the 1980s and 1990s due to the AIDS epidemic. Felix Gonzalez-Torres wrings out every piece of meaning from a simple pile of sweets, encasing us in intimacy, mortality, grief, and political dissent.

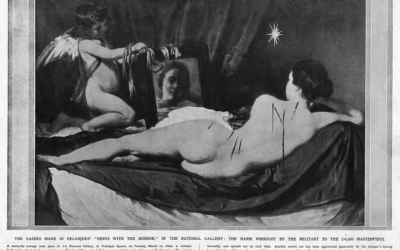

4

The personal and political crossroads of sexuality are also a central concept of Nan Goldin’s photographic oeuvre, in particular her defining series The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. The work is comprised of around 700 candid snapshots involving the artist, her friends, lovers, and strangers. Having undoubtably influenced other confessional photographers like Petra Collins and Sarah Bahbah, the photographs in The Ballad deploy saturated colour and close-cropped frames to invite us in to a world of love, drugs, sex and clubs. We are not seeing and experiencing intimacy between just two people, but between a clan which has forged its creed out of the basic human need for connection. Goldin reflects that she and her chosen family were “bonded not by blood, but by a similar morality, the need to live fully and for the moment.”[1] Like most photography, the series captures the zeitgeist of a particular place and time – the underground scene of New York in the 1970s and 1980s – and as such is a vehicle for heady nostalgia. Like Gonzalez-Torres’s work, there is pain and loss underwritten in the photos, and the omnipresent threat of AIDS is like its own character in the series. Set to an evocative soundtrack featuring James Brown, Petula Clark and the Velvet Underground, the photographic suite shows us both the life, and death, of intimate relationships with people who change, move on, and pass away. Speaking with Goldin thirty years after The Ballad was first shown, Sean O’Hagan observes that it is “now imbued with a deep sense of loss that people seem to connect with deeply.”[2] This encapsulates the core of why intimacy is still such a powerful and popular subject in art today – the ability to relate to those feelings is timeless.

5

Being separated from friends, far away from family, and physically as well as socially isolated by a global pandemic, has made the notion of intimacy all the more ripe for consumption. How do we meet this universal need when it poses a risk to our own health, and the safety of others? Lola Gil reflects on this in her new series, ‘Intimate Flowers Bloom.’ A series of surrealistic portraits embodying echoes of Magritte, Dali and Georgia O’Keefe, the work explores the way we navigate and define our own identities through our relationships with others. Gil says, “These new paintings naturally evolved through subconscious vision, during a collapse with a close relationship, life in isolation, and the powerful decision to be my own source of strength.”[3] Like any artist investigating our collective notion of intimacy, Gil makes the personal journey of self-discovery and self-awareness public. It’s something everyone can recognise in themselves – forging a relationship with the ‘self’, that difficult, prickly, elusive entity that lives within all of us. Whether we do it through mediation, holding hands on the train, social media, sex, or getting high, we’re all searching for the same thing – connection. And in art, sometimes, we find it.

6

Images:

- Photos by Hannah Lafollette Ryan, ,https://www.instagram.com/subwayhands/

- Auguste Rodin, The Cathedral, 1908. Stone, 64 x 29.5 x 31.8 cm

- Tracey Emin, It Always Hurts, 2005. Appliqué blanket, 283.6 x 223 cm

- Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), 1991. Candies in variously colored wrappers, endless supply. Overall dimensions vary with installation. Ideal weight: 175 lb.

- Nan Goldin, from The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, 1979-1996. Slide installation with 690 35mm color slides, sound, 45 min. looped

- Lola Gil, You Rang, 2020. Oil & acrylic on canvas, 61 × 45.7 × 5.1 cm

[1] Interview with Sean O’Hagan in The Observer, published 23/03/2012. ,theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/mar/23/nan-goldin-photographer-wanted-get-high-early-agen[2] As above n[3] ,https://www.lolafineart.com/intimate-flowers-bloom

Related Articles

Weekend Viewing: 13-15 January

It's a new year and there is a brand new lineup of shows opening around the world . Here are some of my top picks for exhibitions to check out this weekend, both online and in person. From biennials to blockbusters and everything in between, this short list will...

My Robot Could’ve Made That

There is a well-known book on modern art called “Why Your Five Year Old Could Not Have Done That.” It speaks to the once-common dismissals of abstract and ‘primitive’ styles of art as childish; art that we now prize above any other genre. But perhaps the next...

Just Stop.

Why using art as a vehicle for protest isn't the solution There’s been a lot of art in the news lately, but not necessarily for the right reasons. We’re used to seeing Picasso, Van Gogh and Munch’s names splashed across the pages of newspapers and the internet, but...