Written by Harriet Maher

September 9, 2021

NFT – it’s the latest art world buzzword (or words, meaning ‘non-fungible token’) – and it’s dragging us all, like it or not, into the future. While these tokens have been around for some time, with the earliest appearing during the 2017 cryptocurrency boom, they are suddenly experiencing a renaissance. And their emergence into the mainstream consciousness this year is no coincidence. With the closure of galleries due to a global pandemic and increasing financial strains, NFTs as a digital medium have become a way for collectors, artists and audiences alike to participate in a ‘metaverse’ of new cultural experiences.[1] With their newfound popularity, there has been a myriad of reports on sales, profits, and the mechanics of NFTs for artists, but what are the actual implications for the industry? Not just for artists, but for galleries, museums, collectors and curators? Conservation, security and display are all concerns that have been raised, but the allure of lucre seems to overshadow all else. NFTs are being heralded as a “paradigm shift for digital art and other forms of online media” by Sotheby’s, one of the many parties cashing in on this latest trend, but what’s behind the hype? It all seems rather obscure, a lot of smoke and shadows, mirrors and screens; more theory than art.

https://video.wixstatic.com/video/102328_c25eabcc87014b518633ba7f2f497f22/720p/mp4/file.mp4Valuart Banksy Collection, Spike. MP4: 22.1MB, 03:12. Minted 30 July 2021. Edition 1/1

My first exposure to blockchain technology and NFTs came, like most of us, from the recent mainstream explosion of cryptocurrencies, and enthusiastic lectures from my partner about the virtues of a decentralised marketplace. For an arts graduate, this all seemed too niche, technical, inaccessible. What’s the difference between an NFT and a digital artwork? How can you own a piece of the blockchain? What IS the blockchain???? Surprisingly, the best explanation I found for this (or maybe it’s not surprising at all) was on Sotheby’s website, in an article accompanying their latest auction of NFTs. According to the auction house giant, “in its simplest explanation, blockchain is a digital, decentralised, permissionless ledger.”[2] An NFT is an entry in this ledger, and it represents a one-of-a-kind asset – hence its “non-fungibility.” This can be a digital asset – a file, for example – or a physical one. The owner of the NFT owns the proof, if you will, that they hold the one and only original of that asset.

Another popular way of looking at NFTs is as “cryptographic trading cards” – collectibles that give the owner a certain status level, that are designed to change hands frequently, and which accrue most of their value over time, rather than at the peak of their popularity. One of the biggest NFT collections is the NBA’s Top Shot offering, comprised of collectible ‘moments’ from NBA history that can be bought and traded for profit. While this seems like a fairly logical progression from traditional trading cards, which were generally associated with games and sports, it’s less clear where art fits into this metaverse.

There are obvious incentives for both artists and collectors to circumvent the traditional gallery, exhibition and auction house loop by participating in the decentralised marketplace of cryptocurrency. The usual barriers to entry don’t exist; you don’t need to be physically present at gallery openings, and while the headlines are raving about millions of dollars in sales, in reality anyone can buy an NFT without emptying their coffers.

They are the latest iteration in a series of democratising impulses in art, and they are revolutionising the market on all fronts.

The desire to share art more readily and freely is not new – from cave to fresco, then to canvas, and now the digital sphere, NFTs are simply the latest innovation in our ability to move and share art.[3] And as art becomes more easily accessible to more people, different types of art, and artists, are imported into the zeitgeist. No longer are Pollock and Rothko the highest fetching auction fodder; now, artists can be anyone, from anywhere, even anonymous. Although the highest selling NFT, which thrust the market into the limelight in March 2021, is by a middle-aged white man from South Carolina known as Beeple, others are cashing in on the sudden rush to invest. Cuy Sheffield, head of cryptocurrencies at Visa (who recently entered the NFT game with a $150,000 purchase of a CryptoPunk), writes that he collects mainly NFTs by black artists, and that he sees them as a vehicle for what he calls a ‘black digital renaissance.’[4] Sheffield sagely points out that the gatekeepers of culture have been predominately white art institutions, museums, and historians who have tended to overlook contributions from black artists, both past and present. “Over the past ten years,” he says, “only 1% of the global art auction market was spent on work from Black artists.”[5] However, in the NFT boom, it is not (at least, not predominantly), art galleries, museums and art historians who determine and influence the value of artwork. Instead, it is consumers of internet culture who decide, and in turn, this generates a much larger and more diverse audience of buyers than a traditional gallery show would reach – even one that features online. Significantly, NFT platforms like OpenSea and NiftyGateway allow artists to sell directly to their audience, rather than engaging with a fee-charging middle man. Although NFT marketplaces do charge users ‘gas’, or sale fees, they are fractional (2.5%) when compared to around 10% commission for the top tier auctions at Sotheby’s or Christies.

One of the most alluring things about NFTs for artists is their ability to link money back to the original creator, as part of the smart contract. When a work is sold by an artist through an auction house, they receive a portion of the proceeds (with the auction house taking their aforementioned slice of the pie). If, in five years’ time, the buyer decides to sell the work, noticing that it has doubled (or more), the artist sees none of that profit. With NFTs, however, the artist can include royalties in the contract, so that with each subsequent sale of their work, they continue to be paid for its increasing value. Franky Aguilar, who created the instantly popular ‘Sup Ducks’ after seeing the success of other NFT projects, made $1.5 million within 48 hours of the series’ release. All of them were quickly flipped for many times their original price, and Aguilar got a cut of the royalties with each resale.[6]

Franky Aguilas, Sup Duck #1928. Minted 17 July 2021. Unique edition of 10,000

Not only do artists benefit from the freedom, independence, autonomy and democracy of the NFT marketplace, so too do buyers. While your average public servant or blog writer might not be able to stomach $69 million for the highest fetching NFTs (or even $11 million for a coveted CryptoPunk), there are NFTs for all budgets. But why would you want to buy an NFT, when you can’t even hang it on your wall? Can’t you just download the digital file associated with it for free, anyway? Well, not exactly.

NFTs are, by definition, unique. Being non-fungible means they are not exchangeable for anything else of equal value. These virtual tokens are about more than just owning the work, or making a pretty penny. As with the traditional art market, collecting NFTs is a way of accruing cultural capital. Cuy Sheffield explains that “the collector of the NFT is purchasing a direct, social connection to the artist…that you don’t get by screenshotting or downloading their work on your own. This creates a powerful form of social signalling and incentive alignment between collectors and artists.”[7] Buying a fake, or downloading the same image for free, might look to the untrained eye like the same thing as purchasing the original NFT. But what’s missing from these fraudulent or free transactions is the connection, the clout, the associative status that comes with splurging on the real deal. A writer at Fortune put it best:

“Rolexes and Lamborghinis are so yesterday. NFTs are the new digital ‘flex.’”[8]

LarvaLabs, CryptoPunk #7523 . 24 x 24 pixels. Minted 23 June 2017. Edition 1/1

One of the best examples of this digital flex is the collection known as CryptoPunks – profile pictures (or PFPs) that were first minted in 2017. They have come to stand as the symbol of NFTs, in many ways, embodying the viral nature, the early experimentation, anonymity and indeed ‘punk’ attitude of the market, and cryptocurrencies more generally. A collection of 10,000 24×24 pixel images, CryptoPunks vary in value and rarity. Each comes with their own attributes, and no two are alike, ensuring their scarcity and therefore intrinsic worth. Their desirability stems from our timeless and perpetual need, as humans, to define ourselves both as individuals, but as part of a collective. CryptoPunks allow their owners to be part of something bigger, something avant-garde and cutting-edge, while at the same time defining them as unique. And, unlike a work of art that might promise the same kind of status generation, NFTs don’t just hang on a wall, or worse, in a vault, unseen by most. They are digitally public, hyper-visible, a badge of honour for the owner. They ultimately loop back to the idea of conspicuous consumption, and the need to have cultural objects that reflect the collector’s place in the world. [9] They are also traceable, which is increasingly appealing after recent art market scandals of fraud and imitation – like the recent exposure of an ‘antiquities mill’ selling fake artefacts in New York.[10] With NFTs, all future purchases and sales are traceable directly back to the original link, so there can be no question of its provenance. It is built into the blockchain itself, so buyers can see how many times the work has been bought and sold, dating all the way back to its first listing by the creator themselves. This (almost) completely avoids the potential for fakes and frauds; but caution is still necessary. Some works may look like an original CryptoPunk, but a closer look will reveal that they were minted by someone completely removed from the certified artist; someone completely uncertified. And that makes them virtually worthless.

It’s not only individuals who have the opportunity to redefine themselves by virtue of collecting NFTs. The Hermitage, the world’s largest museum, has recently announced that it is minting and selling some of its most prized works (including a Monet and a Leonardo) as NFTs. Mikhail Piotrovsky, the general director of the museum, said in a statement that this was “an important stage in the development of the relationship between person and money, person and thing.” He added that NFTs “create democracy, make luxury more accessible, but are at the same time exceptional and exclusive.”[11] Beyond the marketing ploy, the Hermitage is clearly trying to rebrand itself as an institution that is keeping up with the times, ahead of the curve – and, almost certainly, the money to be gained is not lost on Piotrovsky. Instead of purchasing postcards or umbrellas at the gift shop, the museum’s patrons can buy the works themselves, as NFTs. And this memorabilia can be purchased without the inconvenience of a visit the Russian stronghold.

This does, however, raise one of the first alarm bells amongst the clamour of the NFT boom. The works auctioned by the Hermitage are, of course, not originals of the museum’s, but merely held in their collection. General director Piotrovsky’s signature appears on the NFTs – which, the museum claims, makes each NFT an original work. Copies of the NFTs will also be kept by the Hermitage, which plans to display them this fall in an exhibition centred on NFT art.[12] There are some fairly complex implications for ownership and authenticity here, if making a copy of somebody else’s work makes you an original artist, and therefore entitled to profit from that copy. What, if anything, has the Hermitage added to these masterpieces to make them their own – aside from a signature? Again, in the unchartered world of NFTs, few are pausing to ask these questions, being swept along instead by the flow of cash entering the market.

Pak, Fade. Still of SVG file. Minted 30 May 2021. Edition 1/1

The NFT furore is moving at a pace beyond our control, affording its participants and onlookers very little time to evaluate the long-term implications or possibilities. But NFTs themselves respond to time in an entirely unique way, giving us, I hope, space to breathe and consider them as more than just investment tokens. In many ways, NFTs are the ultimate time-based art. Video art emerged in the 1960s as a vessel to explore time as a medium, as artists experimented with duration, chronology and memory. But the underlying substance of these works remains the same over time, each loop repeating itself ad infinitum, or at least until the medium becomes worn out. Performance, too, is time-based, but being (generally) performed by humans, each iteration will be subtly different, and again, any recordings, visual or otherwise, of the performance, capture the original work but do not evolve over time. But for artists such as Pak, one of the preeminent stars of the NFT medium, time becomes an integral force in their work. Pak’s Fade is a visually enticing, movingly beautiful orb, touted as “a living timepiece about digital permanence and identity.”[13] Seamlessly shifting between various washes of blended colour, Pak describes the work not as a “hosted pixel based image sequence,” stating instead “it’s a procedural infinite resolution animated vector file.” If you can’t quite digest this technical jargon (that makes two of us), try looking at it from a more art historical perspective. In true Whitmanian style, the work contains multitudes; it completes one rotation through its colour gradients every minute. Each time it is transferred to a new owner, or wallet address, it resets and regenerates itself with a new colour gradient. Eventually, over the course of one year, the work will, as its title suggests, fade, and eventually disappear altogether. From my limited understanding, there is no other medium in which these directives for an artwork could be reliably implemented, into perpetuity. Pak, through the magic of the blockchain, is able to explore the concept of time, permanence, and identity in a way that has never been possible before.

terra0 is an artwork and research group exploring decentralised technologies built on the Ethereum network, and their relationship to the physical world, mapping ecologies and their nuances on the blockchain. In their recent work Two Degrees, terra0 has created a smart contract in which the work itself – a 3D laser scan of a German forest – is linked to a NASA server which updates the global temperature annually. When that database shows that the earth’s current temperature has reached more than 2 degrees of the global average, the work will be destroyed. The image says it plainly: ‘If global warming reaches 2C above average this NFT will destroy itself.” Not only is this clearly a statement about the fate of the world’s ecology and economy, with the value of the work being ‘burned’ regardless of the owner’s wishes, it adds a completely new dimension to art. It allows artists not only to create, but to destroy. The ownership of the work doesn’t end when it’s bought, because the artist maintains control through the smart contract. As we’ve seen, this control can be both financial and creative, transforming the art market for artists and creatives.

But it’s not all sunshine and multi-million dollar profits. Despite its claims to democratise and decentralise finance and the market more generally, inequality persists, even abounds, within the cryptocurrency and NFT spheres. Only around 15% of Bitcoin users are women, and only about 12% of the blockchain-hosting Ethereum investors are female.[14] Still, there are some who are seeking to rectify this imbalance. Artist Sarah Meyohas minted Bitchcoin, her answer to the dominant cryptocurrency giant, way back in 2015, predating the launch of Ethereum by five months. When the coins were released on the Ethereum blockchain this year, the artist combined this earlier project with her seminal 2017 work Cloud of Petals.

Sarah Meyohas, Bitchcoin. MP4: 5 MB, 1080x1080px, HD, 00:05. Minted on May 21, 2021. 480 unique works

It’s almost difficult to believe how prescient and incisive this work is when positioned within the current explosion of blockchain-based art. Four years ago, Meyohas employed sixteen men to hand-pick the rose petal they thought was most beautiful from a bunch of roses, and photograph it – resulting in 100,000 petals, 100,000 photographs. The intention was to use human intuition and aesthetic judgement to map out an artificial intelligence algorithm that could learn to generate new unique petals on its own, forever. This work in itself is astounding, but when you consider that this year, when Bitchcoin migrated from its own blockchain to Ethereum, Meyohas ‘backed’ her Bitchcoins with a pressed petal from her earlier project, the mind truly reels.

At first glance this is all tongue-in-cheek, a takeback of Bitcoin for the girls, a way of putting a distinctly feminine stamp on the usually-male dominated space of cryptocurrency. But peel back the layers, and Meyohas has not only minted her own form of currency, but she’s backed it with a tangible asset, also of her own creation – the rose petals of her earlier project. The digital is inextricably linked to the physical, both in word and deed. Each Bitchcoin token has a number on the back that corresponds to the number of the worker who participated in Cloud of Petals and the number of the petal they chose. If the owner of a Bitchcoin chooses to exchange their token for a physical relic, their coin will be destroyed or ‘burned’. As Meyohas puts it, “I want the digital to be able to return the real to us in a new, better way. I want Bitchcoins to trade digitally, but always be connected to the physical world, to bodies in the form of rose petals.”[15]

Although not explicitly about gender, there is at least implicitly an intervention here in the traditionally macho world of cryptocurrency (and art for that matter). Using only men in her Cloud of Petals project was not by accident. Naming her currency Bitchcoin is hardly a coincidence. Meyohas’ practice inscribes gender into the blockchain, carving out a place for perceivably ‘feminine’ attributes – nostalgia, tactility, softness, beauty – in a system where the focus has generally been about profits, progress and numbers.

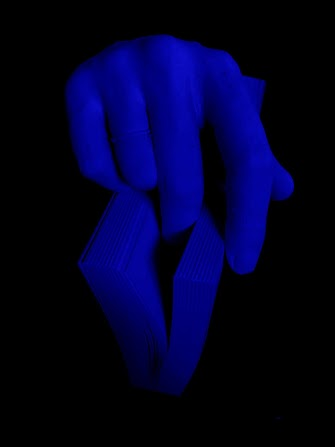

Meyohas is not alone in her efforts to diversify the blockchain space. The 2021 Every Woman Biennial (formerly the Whitney Houston Biennial) featured 272 female and non-binary artists selected through an open-call proposal process. The biennial began in 2014 as a critique of the straight-white-male dominated offerings of the other Whitney Biennial, and this year it has continued to offer female and non-binary artists a space to present their work, this time on the cutting edge of artistic experimentation. While not as critically incisive as Meyohas, the 2021 Every Woman Biennial (EWB) certainly capitalises on the creative and financial autonomy that NFTs offer artists, minority artists in particular. As with video art, which became a key medium for queer and feminist artists in the ’60s and ’70s, NFTs offer a way to supersede the historical trappings of painting, sculpture, even performance and video art. It affords women and non-binary artists greater ownership over their work, plus the assurance that they will continue to benefit financially from future sales. Of course, this applies to all artists who are creating and selling NFTs, but particularly for female and non-binary artists, these same opportunities may not be as readily available to them in the traditional art market.

Mallory Breiner, Blue Hand in Book. Exhibited in Every Woman Biennial 2021. Edition 1/1

While the EWB aims to showcase as many female and non-binary artists working in the NFT space as possible, there are still inequalities in the market outside of gender. It would be easy to assume, from our privileged standpoint of a developed, culturally aware and educated milieu, that NFTs herald a transition from stuffy, exclusive art clubs to a new era of digital enlightenment. Robert Alice, an artist and curator working in the metaverse, boldly claims that NFTs, ‘in their networked community undoubtedly stretching across all corners of the world, stand as the iconic symbol of this transition”[16] But grand, sweeping statements like this risk overstating the access to the kind of cultural capital associated with NFTs. While the barriers to entry are low, they are not completely abolished. NFTs are still a luxury item, an investment, something that only those with spare time, spare capital and a viable internet connection (and a crypto wallet) can partake in. While we might think of the internet itself as a benevolent democratising force, in reality only around 53% of the global population is online, and 47% in the developing world. The blockchain is still a playground for the rich and privileged, despite its claims to openness.

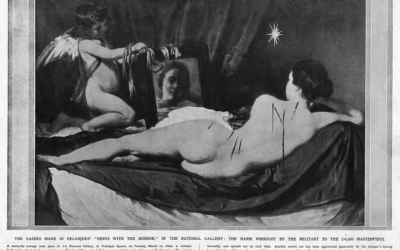

There is a lot to be said for the proof of ownership, validity and authenticity of NFTs. With the contract permanently listed on the blockchain, on public record, as well as any transactions, the works can always be traced back to their original creator. But that doesn’t mean that some aren’t trying to make a quick buck off the current bull run. One NFT recently for sale features a CGI rendering of Banksy’s Spike slowly spinning in the long light of a sunset. It appears to twirl over mountains and water as Italian opera singer Vittorio Grigolo sings the Puccini aria “E lucevan le stelle.” But Banksy himself had nothing to do with this work. It is instead being sold by Valuart, a platform set up to link owners of desirable artworks with other creatives and potential buyers. The buyer of the Spike NFT will also receive extra perks, including a trip for themselves and a guest to see the physical Spike work in Switzerland, as well as a dinner with Grigolo and his other Valuart cofounders, Etan Genini and Michele Fiscalini. This all sounds very alluring and exciting, a real smorgasbord of culture, but copyright lawyer Jeff Gluck of CXIP Labs, a new platform set up to enable NFT creators to effectively ‘blue tick’ their work, claims that Banksy might have grounds to sue if his permission wasn’t gained by Grigolo and his cronies. “The rights to create an NFT of an artwork are held by the creator, the copyright holder – not the person who possesses the artwork.”[17] Valuart beg to differ. Their website proclaims: “our unique NFT artworks (are) derived from the masterworks of some of the greatest artists of all time. All our NFTs are based on the original artworks owned and/or created by our partners, that we couple with compelling storytelling and artistic crossovers to create a unique experience for you.”[18] But Valuart’s ‘partners’ are not the original artists, so what are they really selling? Art, or the experience? In many ways, art has always been about the experience and the cultural capital it carries, rather than the object itself. And in the post-information age, where objects are no longer the most coveted markers of status (at least not consciously) because of their sheer availability, the experience is what brings the most clout. Buyers are offered not only full commercial rights to the NFT, but access to an exclusive club which often offers further content down the line, a brand that collectors can buy into.[19] So, not only are the Valuart founders capitalising on the Banksy brand, but on multiple other cultural forces – opera, Switzerland, comp flights and exclusive dinners.

And they’re not the only ones. A collector who goes by the name Pranksy dropped $335,000 in crypto on what he believed was Banksy’s first-ever NFT. But, just as with the Spike NFT, Banksy had been nowhere near it. In fact, someone had reportedly hacked the pseudonymous street artist’s website so that it appeared to be a genuine offering.[20] In this case, at least, the buyer was able to recoup most of the funds from the imposter, who refunded the entire value of the sale minus the $7,000 transaction fee after Pranksy tracked them down. However, it’s unlikely all potentially duped buyers will be as lucky, and it raises questions about the real validity that NFTs claim to offer. Given the sudden uptake in NFT minting, buying and trading, there will be many who don’t have a full understanding of how the technology works (and I count myself in that number). Without knowing how to look up the smart contract that links the work back to its original creator, buyers are putting themselves at risk of being defrauded by internet pranksters.

These smart contracts, while purporting to be more secure, traceable and able to be authenticated, are, according to some observers, precarious in and of themselves. Anil Dash, who first proposed the concept of NFTs in 2014, points out that when someone buys an NFT, they’re not buying the actual digital artwork; they’re buying a link to it. “And worse, they’re buying a link that, in many cases, lives on the website of a new start-up that’s likely to fail within a few years. Decades from now, how will anyone verify whether the linked artwork is the original?”[21] Despite the current hype around blockchain technology and cryptocurrencies as an integral part of the world’s move towards the future and a decentralised marketplace, there are inherent flaws in the system. As Dash points out, the technology itself is fallible and susceptible to market changes. And ARTnews writer Shanti Escalante-De Mattei agrees:

“NFTs were supposed to be a tamper-proof ledger that authenticated and defined original digital works, which could offer artists royalties as the work was traded in perpetuity. But now it’s clear that the technology used in this $2.4 billion industry is poorly constructed and can’t deliver on its promises.” [22]

Reliance on technology has its drawbacks. Accessibility to valuable works of art relies on that technology being available at any time, into perpetuity. If the platform on which the NFT is hosted fails, if the server they are stored on goes down or is hacked, then the file is lost, or at least temporarily irretrievable. It is arguably too early to know the full scope of the blockchains’ use for creating and storing these tokens, and whether it really is more secure than having a collection under lock and key. It is also too early to know how NFTs will last into the future – how they will be preserved, conserved, maintained and displayed for future generations. Regardless of whether this is the purpose of NFTs, it is something that various collectors and galleries have pondered. “The complexity of maintaining these kinds of works is beyond what one needs for a painting or a print,” says Kelani Nichole, founder of Transfer Gallery, a space which specialises in computer-based artworks. She goes on to say:

“All conservation of time-based media essentially focuses on the artist’s intent, so a conservator will go deep into the process with an artist and talk about things like the environment that they used to build their work….We talk to the artist about the way they use software and about how they want their work displayed.”[23]

While this works for NFTs that are being displayed by galleries, once they are transferred to a private owner, there is no guarantee that these standards of display and conservation will be upheld. Even galleries, despite their best efforts, can’t always overcome the challenges posed by NFT display. At the aforementioned Every Woman biennial earlier this year, hosted by Superchief Gallery, the difficulties were on display for all to see. In the ‘black cube’ of the gallery, flat-screen TVs and projectors lined the walls in a salon-type display, playing the NFTs on individual loops. The usual wall labels were replaced by QR codes, but with the gallery’s ironically poor WiFi connection on opening night, Wendy Vogel reports, “it was anyone’s guess when and on which screen a work would appear.”[24] Not only does this affect the viewer’s and prospective buyer’s experience of the works, it detracts from the artist’s integrity and fails to reflect the time and effort put into the visual creation of the work. Simply showing digital art on a screen doesn’t equal an appropriate means of display. Like a lot of time-based or conceptual work, NFTs have evolved to exist outside the traditional gallery space, even the traditional marketplace. Whether that bodes well or not for their longevity is a different question.

https://video.wixstatic.com/video/102328_d0cbe298ae8e4d05b4cb8702da54b7a2/480p/mp4/file.mp4terra0, Two Degrees. 10630 x 14586 pixels. Minted 12 May 2021. Edition 1/1

Aside from authenticity, security and display, there is one particularly large elephant in the NFT market-room – the environment. After the initial heady rush of NFT minting, selling and buying, some were quick to point out the impact this technology has on climate change. This is a moral sore point for many artists (and non-artists), a number of whom have begun to look for ways to offset their NFT-sized carbon footprint. Beeple says his artwork will be carbon “neutral” or “negative,” meaning he’ll be able to completely offset emissions from his NFTs by investing in renewable energy, conservation projects, or technology that sucks greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere.[25] However, the environmental cost of NFTs is less the result of the creation and exchange of the works themselves, and more an inevitable outcome of the entire cryptocurrency system. Most NFT marketplaces, like Nifty Gateway and SuperRare, run on Ethereum, which is produced by highly energy-hungry ‘miners’ contributing the blocks which make up the blockchain (and that, dear readers, is the extent of my understanding on that). The immense use of power to run these machines is what contributes to their negative environmental impact. But just what proportion of these emissions can be blamed on NFTs, and the people who create, buy and sell them? According to Joseph Pallant, founder of the non-profit Blockchain for Climate Foundation, figuring out the culpability of NFTs is a little bit like calculating your share of emissions from a commercial plane flight.[26] By travelling on the plane, you are indubitably contributing to carbon dioxide emissions. However, even if you hadn’t bought the ticket, the plane would more than likely have taken off anyway, with the other passengers on board, and someone else sitting in your seat. Despite the criticism levelled at the NFT and crypto marketplace, and the retreat by a number of artists from this space to higher moral ground, Pallant confidently said earlier in 2021 that “I think in the next year, year and a half, the emissions will be a non-issue.”[27] This may be because artists like Beeple have vowed to offset all carbon emissions produced by the making of their work, or that galleries and collectives like Every Woman claim that their NFT exhibitions are carbon neutral. The reduction may fall to the wider crypto-community, particularly miners, who will need to turn to renewable energy to power their block-building machines. But as the world undeniably heats up, and climate change becomes the number one concern for humanity, Pallant (and the rest of us) can’t afford to be wrong.

For now though, the NFT market is undeniably the place to be and be seen. These tokens are attracting new and uninitiated buyers to the art market, and catapulting artists onto the world stage who would otherwise never have had their work shown at a mainstream gallery. They are making millionaires out of many and affording us a lens through which to view the future of art, ownership and collection. They allow their owners and makers to cultivate their own personal brand, casting references to their financial wealth, technological savvy and participation in the zeitgeist. They are a sudden and unprecedented intervention into the traditional art world, and, despite their shortcomings, they’re not going anywhere.

References

[1] Robert Alice for Sotheby’s catalogue entry, ‘Larva Labs, CryptoPunk #7523’ https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/natively-digital-cryptopunk-7523/cryptopunk-7523?locale=en. Accessed 25 August 2021[2] NFTs: Redefining Digital Ownership and Scarcity. Sotheby’s, 6 April 2021http://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/nfts-redefining-digital-ownership-and-scarcity?locale=en. Accessed 13 August 2021[3] NFTs: Redefining Digital Ownership and Scarcity. Sotheby’s, 6 April 2021 http://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/nfts-redefining-digital-ownership-and-scarcity?locale=en. Accessed 13 August 2021[4] Cuy Sheffield, ‘Why I’m Collecting Black Crypto Art’, Medium, https://medium.com/@cuysheffield/why-im-collecting-black-crypto-art-c3cbba939d64. Accessed 25 August 2021[5] Ibid.[6] Shanti Escalante-De Mattei, ‘The Future of NFTs: How PFP Based Projects Took Over the Market,’ ARTNews, 25 August 2021. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/pfp-nfts-future-market-1234602384/#recipient_hashed=9c4f9fca100fb8d375a11612e7dcb17dfd5e6d4832c926662273d9570f3e77c8. Accessed 26 August 2021[7] Cuy Sheffield, ‘Why I’m Collecting Black Crypto Art’, Medium, https://medium.com/@cuysheffield/why-im-collecting-black-crypto-art-c3cbba939d64. Accessed 25 August 2021[8] Olga Kharif, Vildana Hajric, Justina Lee and Bloomberg, ‘Rolexes and Lamborghinis are so yesterday. NFTs are the new digital ‘flex.’’ Fortune, 29 August 2021. https://fortune.com/2021/08/28/rolex-lamborghini-nft-comeback-digital-flex/. Accessed 29 August 2021[9] Ibid.[10] Colin Moynihan, ‘He Sold Antiquities for Decades, Many of Them Fake, Investigators Say’. The New York Times, 25 August 2021, updated 01 September 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/25/arts/design/fake-antiquities-investigation.html. Accessed 07 September 2021[11] Tessa Solomon, ‘Hermitage Museum to Sell Money, Leonardo Paintings as NFTs’. ARTnews, 27 July 2021. https://artnews.com/art-news/news/hermitage-museum-nfts-monet-leonardo-1234600031/ accessed 13 August 2021[12] Ibid.[13] Pak, Fade 2021. Sotheby’s catalogue entry, https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/natively-digital-a-curated-nft-sale-2/to-be-announced. Accessed 31 August 2021[14] Wendy Vogel, ‘Every Woman Biennial, “My Love is Your Love”, Art-Agenda 21 July 2021. https://www.art-agenda.com/features/409542/every-woman-biennial-my-love-is-your-love accessed 13 August 2021[15] Sarah Meyohas interviewed by OpenSea blog, June 16 2021. https://opensea.io/blog/interviews/artist-interview-sarah-meyohas/. Accessed 1 September 2021. n[16] Robert Alice for Sotheby’s catalogue entry, ‘Larva Labs, CryptoPunk #7523’ https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2021/natively-digital-cryptopunk-7523/cryptopunk-7523?locale=en. Accessed 25 August 2021[17] Shanti Escalante-De Mattei, ‘Banksy’s Chunk of Israeli West Bank Barrier to be Auctioned as NFT.’ ARTnews, 26 July 2021. http://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/banksy-palestine-auctioned-nft-1234599971/ accessed 13 August 2021[18] Valuart.com Accessed 25 August 2021[19] Shanti Escalante-De Mattei, ‘The Future of NFTs: How PFP Based Projects Took Over the Market,’ ARTNews, 25 August 2021. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/pfp-nfts-future-market-1234602384/#recipient_hashed=9c4f9fca100fb8d375a11612e7dcb17dfd5e6d4832c926662273d9570f3e77c8. Accessed 26 August 2021[20] Anny Shaw, ‘Were Banksy and Pranksy both pranked in $330,000 NFT sale?’ The Art Newspaper, 31 August 2021. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/were-banksy-and-pranksy-both-pranked-in-usd330-000-nft-sale. Accessed 06 September 2021. n[21] Anil Dash, ‘NFTs Weren’t Supposed to End Like This,’ The Atlantic, 2 April 2021. https://www.google.com/au/amp/s/amp.theatlantic.com/amp/article/618488/ accessed 13 August 2021[22] Shanti Escalante-De Mattei, ‘Can the Weaknesses of NFT Technology Be Fixed?” ARTnews 29 July 2021. http://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/nfts-broken-technology-1234600107/ accessed August 13 2021[23] Ibid.[24] Wendy Vogel, ‘Every Woman Biennial, “My Love is Your Love”, Art-Agenda 21 July 2021. https://www.art-agenda.com/features/409542/every-woman-biennial-my-love-is-your-love accessed 13 August 2021[25] Justine Calma, ‘The Climate Controversey Swirling Around NFTs’, The Verge 15 March 2021. https://www.theverge.com/2021/3/15/22328203/nft-cryptoart-ethereum-blockchain-climate-change. Accessed 26 August 2021[26] Justine Calma, ‘The Climate Controversey Swirling Around NFTs’, The Verge 15 March 2021. https://www.theverge.com/2021/3/15/22328203/nft-cryptoart-ethereum-blockchain-climate-change. Accessed 26 August 2021[27] Ibid.

Related Articles

Weekend Viewing: 13-15 January

It's a new year and there is a brand new lineup of shows opening around the world . Here are some of my top picks for exhibitions to check out this weekend, both online and in person. From biennials to blockbusters and everything in between, this short list will...

My Robot Could’ve Made That

There is a well-known book on modern art called “Why Your Five Year Old Could Not Have Done That.” It speaks to the once-common dismissals of abstract and ‘primitive’ styles of art as childish; art that we now prize above any other genre. But perhaps the next...

Just Stop.

Why using art as a vehicle for protest isn't the solution There’s been a lot of art in the news lately, but not necessarily for the right reasons. We’re used to seeing Picasso, Van Gogh and Munch’s names splashed across the pages of newspapers and the internet, but...