Written by Harriet Maher

March 10, 2021

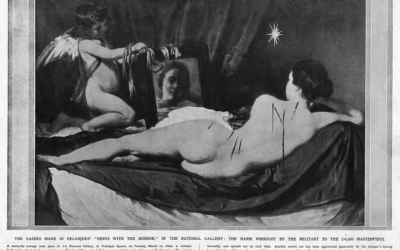

A woman walks into an art gallery – it sounds like the beginning of a (terrible) joke, but in fact, for the woman, the gallery, and many of its patrons, it was the beginning of a nightmare.

The sordid tale unfolds in ‘Made You Look: A True Story of Fake Art’, a recent Netflix documentary that examines a shocking case of art fraud. The sale of $80 million dollars worth of fake abstract-expressionist paintings by the esteemed Knoedler Gallery in New York between 1994 and 2008 rocked the entire ecosystem of art, and exposed many of its shadowy inner workings to the rest of the world. For many viewers, this will be a key insight into the delicate machinery of the art world, which for most people exists behind an opacity of smoke and mirrors. The film raises questions about authenticity, the truthfulness (or lack thereof) of art and its patrons, and the validity of the system in general.

Pei-Shen Qian, the real artist behind the paintings sold by Knoedler Gallery

But what really struck me about this feature-length exposé were the questions it raised about the value of art. What is the measure of art’s value – its monetary value, its cultural and historical worth, or its aesthetic meaning? Does the artist themselves imbue their works with a kind of intrinsic meaning that dissipates when you take away the name of a great artist from the picture? Who decides which paintings, or even artists, have value attached to them? How do we measure the meaning of something so personal and subjective that Ann Freedman, the central figure of the documentary, describes her feelings for works of art as similar to the feeling of falling in love?

To my mind, these are questions that the art world tends to avoid. It is a widely and unquestioningly accepted notion that Michelangelo was a genius, because art history tells us so. We accept that he actually painted the Sistine Chapel, and that it was not some other anonymous tradesman or painter, because the records show us so. We know that an abstract expressionist painting by Jackson Pollock is worth more than one by Corinne Michelle West (a.k.a. Michael West): the auction record for Jackson Pollock is USD $58.3 million.[1] The highest fetching painting by West ever sold was just over USD $80,000.

My question is, why? There are obvious gender and racial biases that pervade the art world, and the world at large, whereby value is attributed to the great white men of history. But aside from these engrained prejudices, what are the parameters of defining a ‘good’ work of art?

Corinne Michelle West, aka Michael West, Untitled [Double-sided] (1970–71).

While I don’t pretend to have a definitive answer to this question, my response would be that it is dealers, galleries and curators who decide the ‘value’ of a work and an artist. These magnates of the industry invest significant amounts of time, energy and money into determining the leading emerging artists of the moment. Art historians, collectors and audiences are like horses lead to water, and then made to drink, when it comes to understanding and patronising art. In their book on art practices that don’t fit neatly into this structural system, David Carrier and Joachim Picasso write:

“It is a well-groomed world governed by a complex bureaucratic system, where artistic output is filtered and tamed by ‘experts’ and then presented to the wider public through the exhibition system.”[2]

Those artists who are given solo shows, whose works hang in the most prestigious galleries, on the whitest of walls, are the ones who will have reviews published about them, who will have collectors with lined pockets come to their champagne-sodden openings, and who, as a result, will be immortalised in the annals of art history. For artists whose work rarely, if ever, leaves their studio, and passes quietly and anonymously into the hands of family and friends, their legacy is destined to be worth virtually nothing.

Art is only art if someone is looking at it, but more importantly, it’s only art if the right person is looking at it.

There is a litany of literature on the topic of art as a commodity (see: Andy Warhol), so I won’t elucidate too extensively on that subject here. The scope of this discussion is unfortunately limited to painting, and cannot account for the paradox of the kind of art that is made which is intangible, unable to be sold in any traditional sense. Suffice to say galleries, dealers and curators have an agenda to fill, and by perpetuating veins of taste that have endured for centuries – art is good if it is by a white, straight man, and even better if that straight white man was troubled in some way, or at least had a premature death – they perpetuate these same stereotypes in art history. When Joan Mitchell approached art dealer Julius Carlebach in the 1950s, hoping he’d sell her paintings, he replied, “Gee, Joan, if only you were French and male and dead.”[3]

Lee Krasner, The Eye is the First Circle (1960), Oil on canvas, 235.6 × 487.4 cm

Despite Carlebach’s small-minded response, recent years have seen a surge in the prices for female abstract expressionist artists. Their rising popularity is thanks in part to the larger movement of feminism, which continues to assert the value of women’s cultural production. The promotion of these artists by galleries and auction houses, however, is not just in service of a social cause. Their art provides an opportunity to invest in more affordable artists, given that the likes of Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock are now beyond the reach of 99% of the world’s population. Which brings me back to my original question: why? The discrepancy in (monetary) value between two direct contemporaries, the husband and wife duo Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, is vast – Pollock’s works have sold for nearly five times the price of Krasner’s. But put two paintings by each artist side by side, and only a true expert or academic could tell you the difference.

In fact, put a fake Mark Rothko in front of a renowned and experienced gallery president and dealer, avid collectors, purported experts and family members of Rothko himself. They will tell you it is beautiful, exquisite, and offer you $8.3 million for it. During the trial that ‘Made You Look’ unpicks, Domenico De Sole, the duped owner of Untitled 1956, was asked by his lawyer if he understood now that the Rothko he bought was fake. Of course, De Sole confirmed he did. The prosecution then asked if that knowledge had any impact on the painting’s value. With a scoff, the Sotheby’s chairman replied, “I think so! It’s worthless.”[4]

The counterfeit painting sold as Untitled 1956 by Mark Rothko.

My point is, the work itself is not what holds intrinsic value, as much as we cleave to this belief. It’s not the cultural and historical significance of the work, nor its contribution to artistic development, which begets such astronomical price tags at auction. It is the culture of artistic genius, the canon of great artists, and the revolving door of influence, money and bias, which sets the bar for ‘quality’ in the art world.

‘Made You Look’ is the proof in the abstract-expressionist pudding.

[1] As at October 2020. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-rising-market-women-abstract-expressionistsn[2] David Carrier and Joachim Picasso, Wild Art. London: Phaidon Press, 2013, p8n[3] https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-rising-market-women-abstract-expressionistsn[4] M. H. Miller, ‘Domenico De Sole, Who Paid $8.3 M. for Fake Rothko, Takes the Stand in Knoedler Trial,’ ARTnews, 28/01/2016. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/domenico-de-sole-who-paid-8-3-m-for-fake-rothko-takes-the-stand-in-knoedler-trial-5733/n

Related Articles

Weekend Viewing: 13-15 January

It's a new year and there is a brand new lineup of shows opening around the world . Here are some of my top picks for exhibitions to check out this weekend, both online and in person. From biennials to blockbusters and everything in between, this short list will...

My Robot Could’ve Made That

There is a well-known book on modern art called “Why Your Five Year Old Could Not Have Done That.” It speaks to the once-common dismissals of abstract and ‘primitive’ styles of art as childish; art that we now prize above any other genre. But perhaps the next...

Just Stop.

Why using art as a vehicle for protest isn't the solution There’s been a lot of art in the news lately, but not necessarily for the right reasons. We’re used to seeing Picasso, Van Gogh and Munch’s names splashed across the pages of newspapers and the internet, but...