Written by Harriet Maher

April 30, 2018

A review of the exhibition by Robert Brain and Kate Just

Chapter House Lane, 1 March – 28 April 2018

Needleman, Feminist Fan is not just a show about two artists exploring the oft-overlooked and undervalued practice of weaving and needlework. It is a succinct and tightly woven analysis of the way in which artistic practice, gender, sexuality, and art history overlap within these two distinct bodies of work.

The artists, Kate Just and Robert Brain, come from different generations, yet both use an artistic technique that has endured for centuries. Robert Brain has employed needlework in his art since the 1950s, building his images freely, without a pattern, and “not a cross-stitch in sight.” Kate Just has incorporated knitting in her practice since 2002, reframing the craft as an artistic, emotive and political tool. Both artists work to dismantle conventional perceptions of craft, particularly needlework, as a domestic hobby, traditionally conceived of as decoration and not as something to be hung on the walls of a gallery.

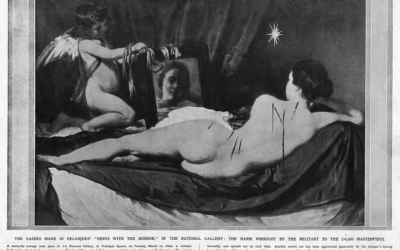

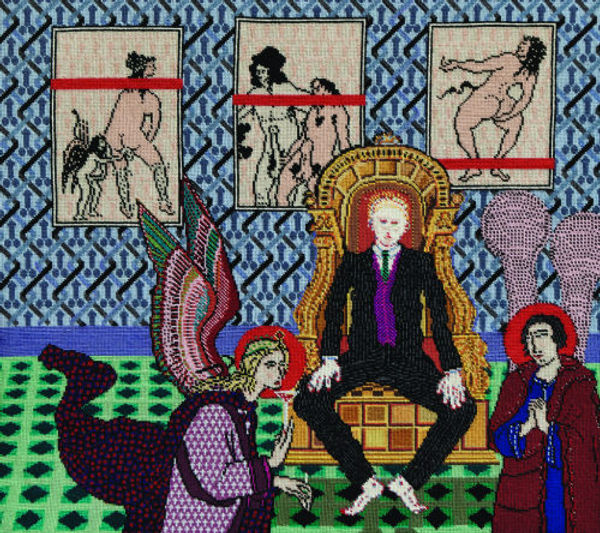

But hung they are, on the soft ochre walls of Chapter House Lane in Melbourne’s CBD, tucked down a laneway next to the imposing St Paul’s Cathedral. Brain’s work, in particular, takes on a decidedly wry stare as it gazes back at the spire and arches of the cathedral, with his humorous incorporation of religious and art historical iconography. The two kneeling figures in London Threesome: Margaret, Robert and Richard (2008-2012, image above) might have knelt above any altar, in any church around the world; but here they pray at the feet of a more contemporary icon – the artist himself. The figure of the angel is a portrait of his friend Margaret Duff, and the saint to his left is Brain’s partner, Richard. Pulling threads of autobiographical material into his work while simultaneously layering the tapestries with art historical references is a consistent theme throughout Brain’s practice, also visible in his work Robert with Girlfriend, Anne Padavini, Dancing in the Belvedere Ballroom, Hobart (2008-2012). The framed images of truncated male torsos in the background of the tapestry obviously reference classical and Renaissance sculpture, but Brain says they also echo images that came to him in dreams, or more accurately nightmares, that he began to have in his late teens when his sexual awakening as a gay man developed. Brain’s tapestries span historical time periods, geographic localities, gendered divisions of labour, and art historical conventions, taking the practice beyond a domestic pastime and into the protracted time of history. But beyond all the seriousness of Brain’s engagement with art history and sexual politics, his works are witty, sardonic, and often very funny.

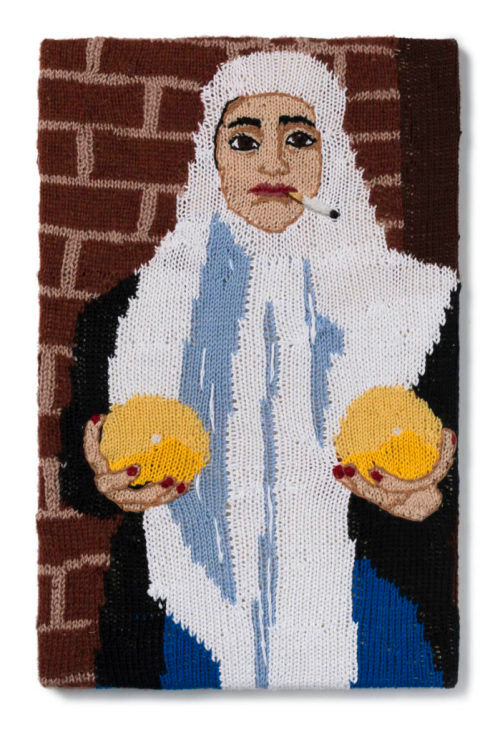

Kate Just likewise celebrates history and blends art historical references in her series Feminist Fan, creating woven portraits of feminist figures she admires. Each portrait is accompanied by a testimony to why they are a feminist hero of the artist’s on her Instagram page, @katejustknits. Using what is traditionally seen as a “women’s” craft, Just elevates the practice of needlework in a similar vein to Brain’s humorous tapestries, and in doing so elevates the profile of the women she admires. The series uses over 10,000 stitches and has taken over 80 hours to complete, making it a true labour of love. In the exhibition at Chapter House Lane, portraits of Sarah Maple, Claude Cahun and Kate Beynon sit comfortably alongside Brain’s art historical allusions and autobiographical musings. The portrait of Sarah Maple, a British visual artist of Muslim heritage, shows her in a traditional hijab with a cigarette hanging nonchalantly out of the corner of her mouth, and two yellow melons held suggestively over her breasts. This gesture within Just’s homage to Maple is a nod to another British artist, Sarah Lucas, who is known for “tough-gazed self portraits with cigarettes, bananas, fish or fried eggs.” Just reinforces the lineage of feminism by drawing together these temporally and geographically distinct artists, and highlighting their tenuous connections to one another. Like Brain, Just walks a line between the personal and the political, a boundary that has become the battleground upon which much of the war of feminism has been waged. These feminist heroes are public figures, their portraits are hung in public places, and the messages which they send to viewers, fans (and foes) around the globe are political, but Just imparts a personal note on each portrait with her message shared via social media. On Maple’s self-portrait, she comments, “Her vision of female identity is one that is complex and layered and doesn’t neatly gel. Most of us can relate to that. Sarah Maple, I’m your feminist fan.”

Curator Louise Clerk’s thoughtful and insightful pairing of these two artists has engendered a show that sheds new light on the art of needlework, and the potentiality it holds for sparking discourse not only around the medium itself and the way it is still being used in contemporary art, but also around the issues that these two artists explore. Within the small scope of the space and the limited number of works (only nine in total), ideas, allusions, juxtapositions and jokes explode off the walls and into public space. But despite the immediacy and urgency of the ideas conveyed in the works, there is a timelessness about them imparted by the labour-intensive nature of needlework, reminding us that some good things really do take time.

Related Articles

Weekend Viewing: 13-15 January

It's a new year and there is a brand new lineup of shows opening around the world . Here are some of my top picks for exhibitions to check out this weekend, both online and in person. From biennials to blockbusters and everything in between, this short list will...

My Robot Could’ve Made That

There is a well-known book on modern art called “Why Your Five Year Old Could Not Have Done That.” It speaks to the once-common dismissals of abstract and ‘primitive’ styles of art as childish; art that we now prize above any other genre. But perhaps the next...

Just Stop.

Why using art as a vehicle for protest isn't the solution There’s been a lot of art in the news lately, but not necessarily for the right reasons. We’re used to seeing Picasso, Van Gogh and Munch’s names splashed across the pages of newspapers and the internet, but...