Written by Harriet Maher

July 30, 2020

Our reality has shifted from the physical to the virtual. Rather than being comprised of a set of chronological events, our timeline is now an endless feed of images, links and articles, all circulating around the core issue of infection and the permeability of bodies. In this virtual realm where the body has become a spectre behind the veil of the screen, women[1] have a unique opportunity to move beyond the confines and strictures that have been tied to their physical bodies for centuries. Now that our physical forms are untrustworthy, unsafe, unclean, susceptible to a virus that does not discriminate between gender, sexuality or culture, can we move beyond the physical to a more democratic space, time, and collective memory? For the arts, the shift towards online exhibitions and the sharing of creative output and knowledge presents an opportunity to journey outside our static ‘timeline’ to other places, even other times. Platforms such as Google Arts and Culture allow us to experience virtual tours of museums we might never have been able to visit in the flesh, such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Palace of Versailles in France. Online, we can even ‘visit’ historic exhibitions, such as the 2015 Venice Biennale, only available in their physical form to an elite audience. During the COVID-19 lockdown in Aōtearoa (New Zealand), where time has been delineated by a gradual descent through ‘levels’ of restricted physical and social liberties, I have been considering the impact of this new virtual ‘reality’ on women artists, art spaces and organisations.

With the closure of physical exhibition venues, educational institutions, and swathes of public space, artists are now turning to the Internet and social media to continue their creative interrogation of our times. For women artists in particular, the impetus to produce work that is resistant to the bounds of institutional space is not new. In the late 1960s and early seventies, grassroots feminist art movements created their own studio spaces, art schools, exhibition venues, and collective arts and crafts groups. These groups and spaces worked collaboratively and tirelessly to raise the visibility of women in the art world, outside of the patriarchal, heteronormative, colonial arts ecologies of the time. In the midst of the collapse of traditional gallery spaces we are currently experiencing, social media platforms have the potential to facilitate a similar kind of awareness-raising online.[2] There is a sense of community and connectedness in online spaces such as Instagram and Twitter, where artists share each other’s work, and cross-reference journals and group exhibitions they have contributed to, or simply have an interest in. Scrolling through someone’s followers, likes, and comments can spotlight new artists and platforms previously unseen in physical spaces, or by the usual gallery audience. The sociality and conviviality of online space offers “a potential way for women to facilitate wider exposure and possible wider recognition of their aesthetic expertise in a cultural sector which remains unequal.”[3] I have lost count of how many new artists I’ve discovered during the lockdown, simply through the interconnectedness of hashtags, online group exhibitions and awareness-raising pages such as @bowdownpodcast and @thegreatwomenartists. Of course, the open nature of online space and its widespread accessibility is not exclusive to women, but given the history of feminist art praxis and its focus on collaborative making, the sharing of knowledge and skills, and rhizomatic connections, women are naturally positioned to flourish in the current climate of online production and display.

The spaces created by women artists online are underpinned by ideas of solidarity and community, and extend beyond barriers of gender to a de-colonisation of space and access. Social media is free and accessible to everyone with a device and an Internet connection, rather than high gallery fees or a “who you know” structure. Of course, it is easy to assume, from our position in developed, connected and industrialised communities, that this access is as integral to daily life as food, water and shelter. But in reality, only 57% of the world’s population has access to the Internet, and it would be a fallacy to argue that online spaces completely eradicate social and physical inequalities.[4] The galleries, institutions and publications that attracted the most “foot traffic” pre-pandemic will continue to draw the largest audiences, as the world looks towards online journalism, criticism, and virtual spaces for arts content. But there is also an opening for new spaces to emerge, and for online traffic to be diverted away from traditional, male-dominated spaces and discourses. The mutability of online space, and the potential for established power structures to be either reinforced or resisted therein, is at once powerful and terrifying. The power, for women artists, lies in the ability to promote, curate and edit their own image and oeuvre through online platforms. The inherent terror stems from the transience of social media, which keeps us pinned to an ever-refreshing present in which collective memory and cultural material is constantly erased by our apps, or even ourselves, in search of the new and the now. The online state of flux prompts a drive to remain ahead of the curve, but also necessitates more permanent interventions of established hierarchies.

One of these interventions involves more and more women writing themselves into history through their social media and online presence. Huni Mancini suggests that this is because “they have intuited that to archive themselves gives their existence validity.”[5] Historically, archives have been carefully maintained by institutions and trained professionals, sanctioned by established centres of power. Today, Mancini writes, “this practice is continued by GLAM institutions who continue to speak for and define marginalised peoples using masculine and colonial concepts of authenticity.”[6] Of course, there are archives – such as the Women’s Art Register – that have redefined these concepts and brought marginalised groups into historical narratives, even written new ones. This essential work was underway long before the rise of COVID-19 and the ubiquity of the internet, but women, and particularly Indigenous women, are increasingly able to document themselves in new ways[7], rather than waiting to be brought into the fold by institutional, or even marginal, archives. Social media takes this one step further as a form of live documentation, an archive of the self. Women artists are able to self-represent, share their work, and position themselves within a trajectory of historical and contemporary work. Many artists curate their feed to include other artists and influences, as well as snapshots from their daily lives. Self-representation for women artists, including Indigenous and queer artists, is an important act of resistance to the exclusive and hegemonic nature of many institutional archives, and is becoming more and more prevalent in the virtual age. Of course, to represent oneself, and to remain outside the margins of history and the contemporary zeitgeist, also presents problems for women artists. There is a risk of potentially remaining invisible in the public sphere (whether that sphere is virtual or physical). Thus, online exhibitions appearing in the wake of COVID-19, which highlight or draw attention to women artists and other marginalised groups, are equally as important as the personal archives and visual online diaries that artists create. One such show, ‘Queer Algorithms,’ presented by Gus Fisher gallery in Auckland, Aōtearoa, showcases local and international artists whose works respond to established systems of exclusion by “reconfiguring new algorithms for change.”[8] This is an apt metaphor for the ways in which online algorithms and platforms are being decoded and recalibrated during this time of physical isolation, to constitute more inclusive and radical spaces for queer artists, women, and Indigenous artists alike.

Fig 1: Jordana Bragg (2016). “What Does Feminism Mean to You?” [1 Image as part of the 10 part limited edition A4 digital print series “Days Since and Again So Soon]. In collection with Wellington City Council, and CPAG, Christchurch, NZ

While the virtual realm allows for constant self-creation, actualisation and renewal, artists continue to look to the past for insight and clarity. At a time when uncertainty is the only certainty, archives provide artists with a framework in which to crystallise their identity. Aōtearoa artist Jordana Bragg claims online space as “one of the best platforms for representation or intentional misrepresentation….It’s Judith Butler 101, the theory of performativity. Online is often my first port of call because it’s in my hand, it’s accessible to me as a sort of weapon of reconstruction.”[9] (Fig. 1) This is particularly powerful for artists whose bodies are perceived as threatening or ‘other’ to patriarchal, colonial, cisgender and heteronormative structures. As we find ourselves physically isolated, our bodies deprived of contact and agency, might we look to shed our skin, in a sense, and explore a post-gender, bodiless existence in which gender and other biases are no longer prevalent?

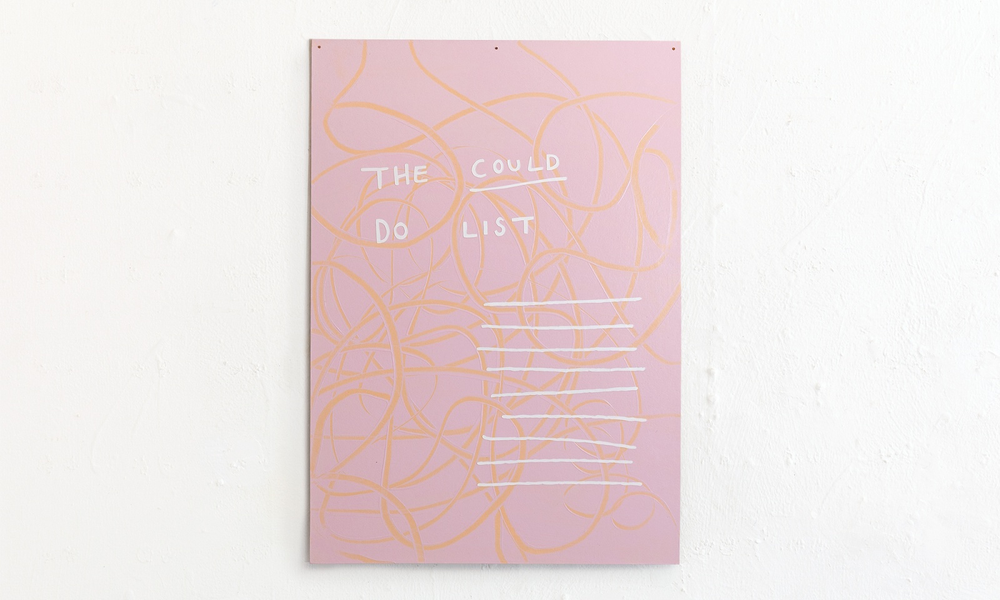

There are myriad other questions that arise from the opacity of the future. What are the implications for the GLAM sector once we move out of lockdown and back to a new ‘normal’? How might artists maintain and develop their practice outside of established hegemonies? What are some of the ways arts professionals can continue to utilise the tools that have served us in this time, to engage with audiences in a more open and inclusive way? Grace Ridley-Smith, manager of McLeavey Gallery in Wellington, Aōtearoa, decided to go ahead with an online exhibition of artist Christina Read’s work, after the physical opening was foreclosed by the nationwide lockdown. Read’s works make an incisive and poignant commentary on the precariousness and ‘queasiness’ of time-management and personal certainty (Fig. 2). Although the work was not made in response to COVID-19, the exhibition speaks to the current collective anxiety about how to measure, manage and spend our allotment of time at home. Despite her decision to exhibit the work online, Ridley-Smith is wary of the translatability of the physical world to the virtual. “Lifting something from the real world and assuming it will work online denies that the digital experience is different from the physical. Time feels longer online. Attention spans are shorter. Competition is fierce. You can’t rely on physical chemistry or ambience… (but) at the heart of the gallery is a desire to remain connected to its congregation. We don’t yet know what the future holds but this experience has given us more tools for ensuring that the door remains open.”[10]

Fig 2: Christina Read ‘The Could Do List’ 2020. Painted paper on board, 590 x 840mm. Exhibited at McLeavey Gallery, 02 Apr – 30 May. Photography by Russell Kleyn.

Other galleries are interrogating this tension between virtual audience engagement and the capacity for real connectedness, even intimacy, in times of physical isolation. George Paton Gallery at the University of Melbourne launched an online group show called ‘A Network of Gestures.’[11] Curated by Mary-Louise Carbone, the exhibition features local artists, many of them female-identifying or non-binary, who recognise that the basic human desire for sentimentality persists even (or especially) in times of isolation. The show explores how intimacy continues to thrive amongst the multitude of screens and tabs that separate us physically, and is concurrent with my feminist investigation into how virtual existence can be a catalyst for radical change. It is born of a search for deeper and more expanded connections, not only to others, but to ourselves.

While we are facing uncertain and difficult times in the arts, the virtual tools that artists and art institutions are now turning to – social media, online archives, self-representation, virtual exhibitions – are evidence of a radical shift towards a more open, accessible and inclusive arts ecology. For women artists in particular, these interventions in the status quo are immensely powerful, even necessary. There is an opening in the veil that has shielded so many female, queer, and Indigenous artists from the public eye, and from the anachronistic lens of history. Already, many are beginning to pierce it.

This article was first published for the Women’s Art Register Bulletin #66. The full publication is available here.

n[1] In this article, the term “women” includes cis,non-binary and trans identities.n[2] Karen Patel, The Politics of Expertise in Cultural Labour: Arts, Work and Inequalities. London: Rowman and Littlefield, 2020, p.108n[3] Ibid, p106.n[4] https://www.oberlo.com/blog/internet-statisticsn[5] Huni Mancini, ‘The Dark Intimacies of Online Romance in Natasha Matila-Smith’s Artwork,’ The Pantograph Punch, 10 January 2020. https://www.pantograph-punch.com/post/touching-the-veiln[6] Ibid.n[7] Ibid.n[8] https://gusfishergallery.auckland.ac.nz/look-through-queer-algorithms/n[9] Ellie Lee-Duncan, ‘The Edited Self: An Interview with Jordana Bragg,’ The Pantograph Punch, 20 November 2017. www.pantograph-punch.com/post/interview-jordana-bragg.n[10] Francesca Emms, ‘Subverted Plans’. ArtZone, April 22 2020, https://www.artzone.co.nz/post/subverted-plansn[11] https://anetworkofgestures.cargo.site/n

Related Articles

Weekend Viewing: 13-15 January

It's a new year and there is a brand new lineup of shows opening around the world . Here are some of my top picks for exhibitions to check out this weekend, both online and in person. From biennials to blockbusters and everything in between, this short list will...

My Robot Could’ve Made That

There is a well-known book on modern art called “Why Your Five Year Old Could Not Have Done That.” It speaks to the once-common dismissals of abstract and ‘primitive’ styles of art as childish; art that we now prize above any other genre. But perhaps the next...

Just Stop.

Why using art as a vehicle for protest isn't the solution There’s been a lot of art in the news lately, but not necessarily for the right reasons. We’re used to seeing Picasso, Van Gogh and Munch’s names splashed across the pages of newspapers and the internet, but...