Written by Harriet Maher

January 30, 2021

Text me back explores the dichotomous relationship between art and language. Pictures and words. Sight and speech. Images and text. The works interrogate an image’s ability to speak in words we don’t know yet, and the possibility for language to imbue an artwork with undiscovered or unimagined meaning.

In the digital age, memes rapidly (d)evolve from a captioned picture, to endless iterations of the caption, to a state where the words themselves are no longer needed. Emojis are their own independent dialect, and words disappear from linguistic ubiquity as quickly as they enter it. At this crucial point in time for artists, writers and audiences alike, how can we approach art in a way that transcends a traditional dichotomy of image/text?

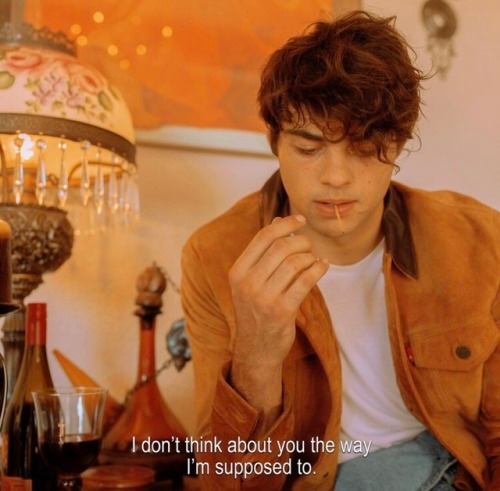

An Instagram post is only as good as the caption, and Palestinian-Australian artist Sarah Bahbah appears to understand this in an instinctive way. Her images are rich in emotive meaning and imbued with contemporary melancholy, teenage longing, loss and desire. On their own, the photographs hint at intense states of mind and intensely specific contemporary worlds. But coupled with their savvy text, mimicking the Instagram caption, they utterly transport the viewer into the newsfeed of the emotions.

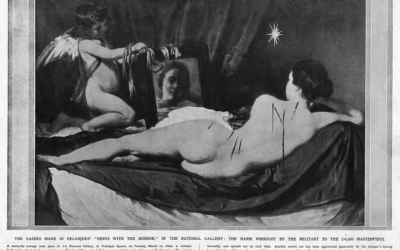

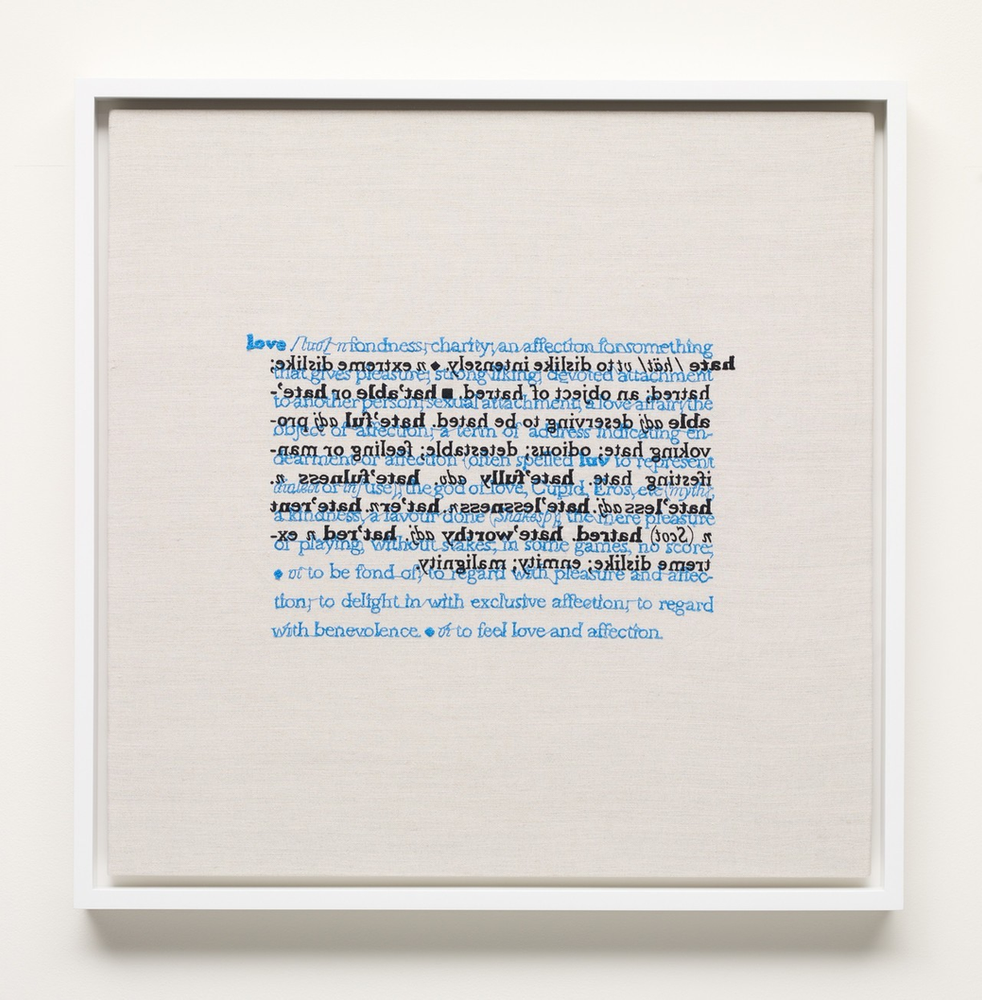

But text can also complicate or separate meaning from an image. As evidenced by Magritte’s now-famous attestation ceci n’est pas une pipe, images are treacherous, and language is a trickster. Reading is more about seeing what is left unsaid, or what is unable to be expressed in words. Writing is more about the gaps between words -the lacunae are where meaning happens. Cornelia Parker grasps this in her text-based work, Love, Hate (verso) from 2017. Dictionary definitions of the two most basic affects, love and hate, are overlaid in blue and black ink on white canvas. The definition of love is written left to right, front to back, while hate is reversed and reflected. At first a simple reading of the ‘rightness’ and ‘goodness’ of love, and the opposite nature of hate, a closer ‘reading’ reveals more layers to the work, literally. By blending the text, both definitions are rendered largely illegible, apart from the occasional word that can be discerned amongst the gibberish. When the viewer focuses their eye on the definition of love, they are simultaneously reading the antonym’s meaning. Parker seems to be asking us, are love and hate really so different? She also complicates the notion of meaning itself – whose definitions are these? Dictionaries are universally accepted as bibles of meaning and truth, but, like anything created by humans, they are (at least to a certain extent) subjective. Parker draws us into her web of woven words, in which signifier and signified are no longer transparent.

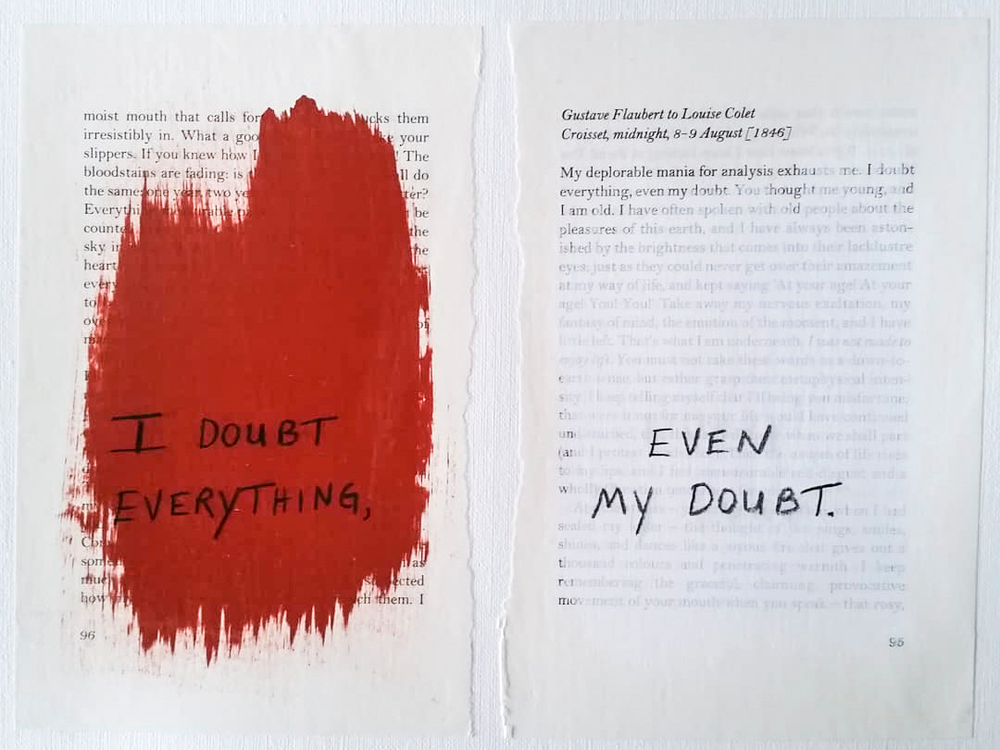

A similar use of text to efface/deface language and meaning comes to the fore in Cynthia Grow’s work on paper, Love Letters – Gustave Flaubert to Louise Colet, Croisset, Midnight 8-9 Aug 1846 (2017). Two pages from a letter written by Gustave Flaubert to Louise Colet are roughly painted over in red and white, partially obscuring the original text. Again, fragments of intelligibility are visible, but the dominant text of the image is Grow’s own – I doubt everything, even my doubt. This calls to mind the unreliability of self, thought and language. Importantly, one of the lines visible from the letter, at the top of the right hand page, reads ‘My deplorable mania for analysis exhausts me.’ The more we read, the more we question the initial meaning derived from the words. Language demands analysis (we can’t believe everything we read), and analysis begets further analysis (we can’t believe everything we think).

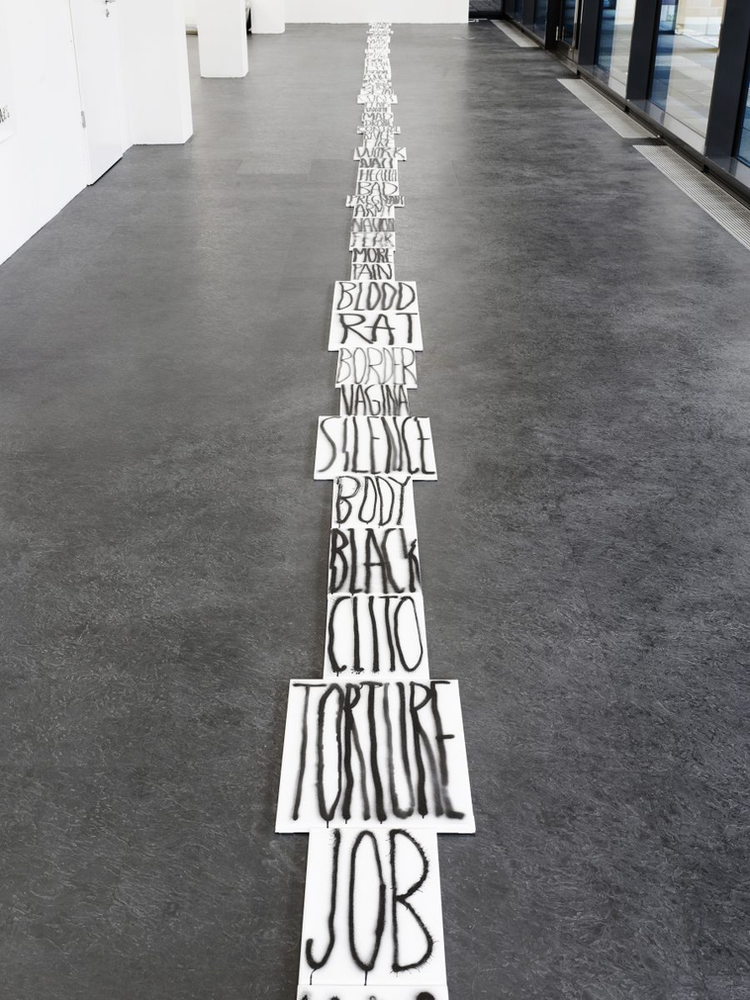

Language, in Anne-Lise Coste’s floor based work Poème de la Douleur (Poem of Pain), elicits the violence of language. Comprising 54 canvases spray-painted with a single word, the poem unfolds across the gallery floor. The work severs the space in two, taking the viewer on a journey through insult, derogation and various assaults on the psyche through language. The meaning is enforced through the particular juxtaposition of individual words which form the whole poem. Presumably, the work could take hundreds of iterations, depending on the order the tiles are laid out in a particular space. Seemingly innocuous words like black, more, and body are interspersed with torture, blood, silence and fear, creating a tense and confronting example of the way words affect themselves, each other, and their audiences, depending on their interrelationships. According to Dortmunder Kunstverein, where the work was shown as part of Coste’s recent show La La Cunt (22 Feb – 3 May 2020), the work is “perhaps a reference to the conflict between specific terms and their potential for varied ascriptions in determining meaning.”[1]

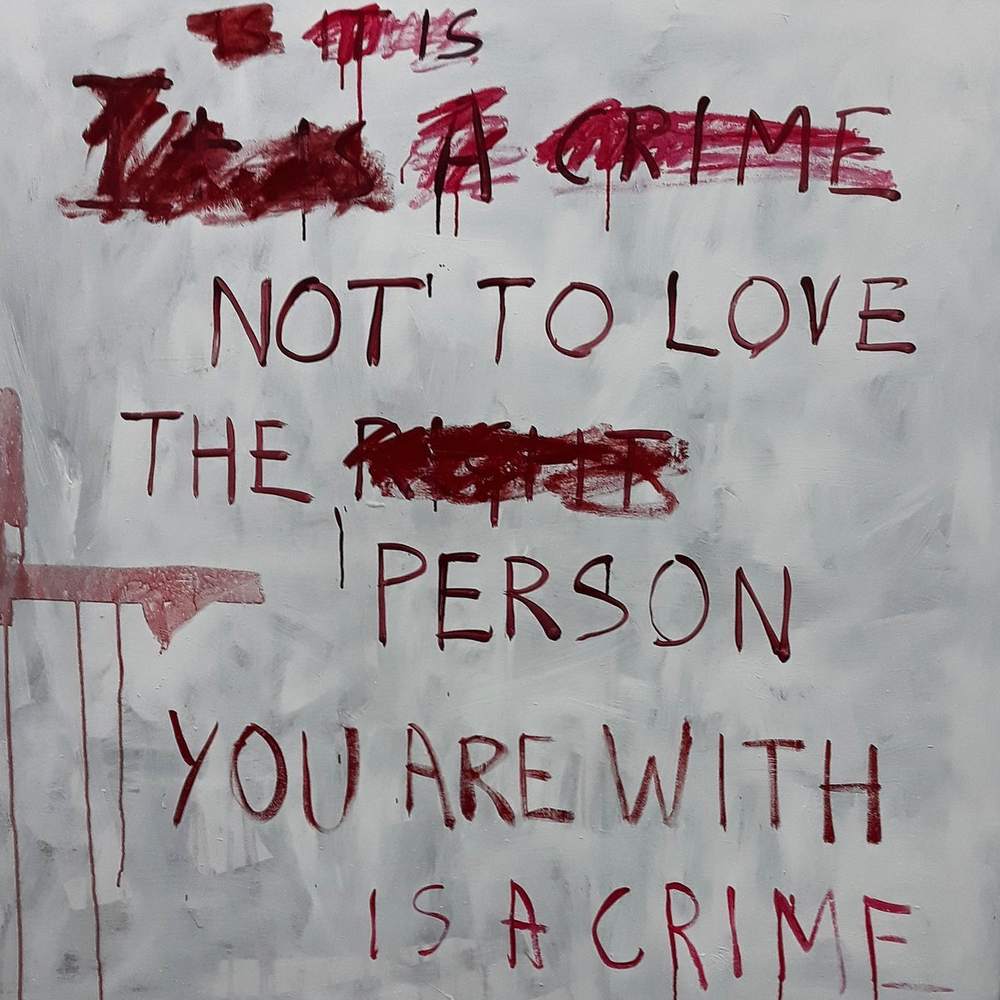

If words elicit violence for Coste, they are weapons of mass destruction for Tracey Emin, whose sweet and sharp epitaphs scar many of her canvases, sketches and embroidered works. Known for her visceral, personal and emotional works, Emin explores her own vulnerability and that of her art, and her painting No Love is no exception. Mistakes, revisions and omissions are made real and visible, accepted and even integral parts of the work. Rather than painting over the initial wording of the work (‘Is it/It is a crime not to love the right person’), pieces of this phrase remain legible, and form part of the final iteration of the work, which reads: “Not to love the person you are with is a crime.” Although similar, built from some of the same building blocks of language, the two phrases come to mean entirely different things. There are at least two works within the canvas, open to the viewer’s fragmented reading of Emin’s amendments and edits of the work. What begins as a question becomes a statement; what could be a judgement of right and wrong becomes an edict on relationships that reads like a universal truth. But Emin reveals that there is no such truth, no such universal; no such right or wrong relationship. The way we cling to language to make sense of our world, to give us direction, to tell us the difference between right and wrong, good and bad, love and hate, are revealed in this work (and others in this essay) to be mere facades of meaning. Constructions of language can be torn down as easily as they are built.

nEmin’s exhibition ‘A Fortnight of Tears,’ in which No Love appeared in 2019, was an exploration of female pain. The unreliability, violence and trickery of language is not gender-neutral, it is often geared towards women and other marginalised groups. As victims of language, women (including trans, queer and non-binary identities) are more inclined to use it as the tool of their reclamation of power. Resisting the singular meaning of words and language speaks to Hélène Cixous’s idea of “l’ecriture feminine.” In The Laugh of the Medusa (1979), Cixous cunningly reads Freud and Lacan through a feminist lens, arguing that women exist outside, or at least in the margins of, Lacan’s Symbolic order. The fact of their sex makes them incomprehensible, less moral, less rational than men. Rather than seeing this as a detriment or impediment to women’s writing, though, Cixous notes that women are freer to move and create within language, rather than being bound to signified meanings.

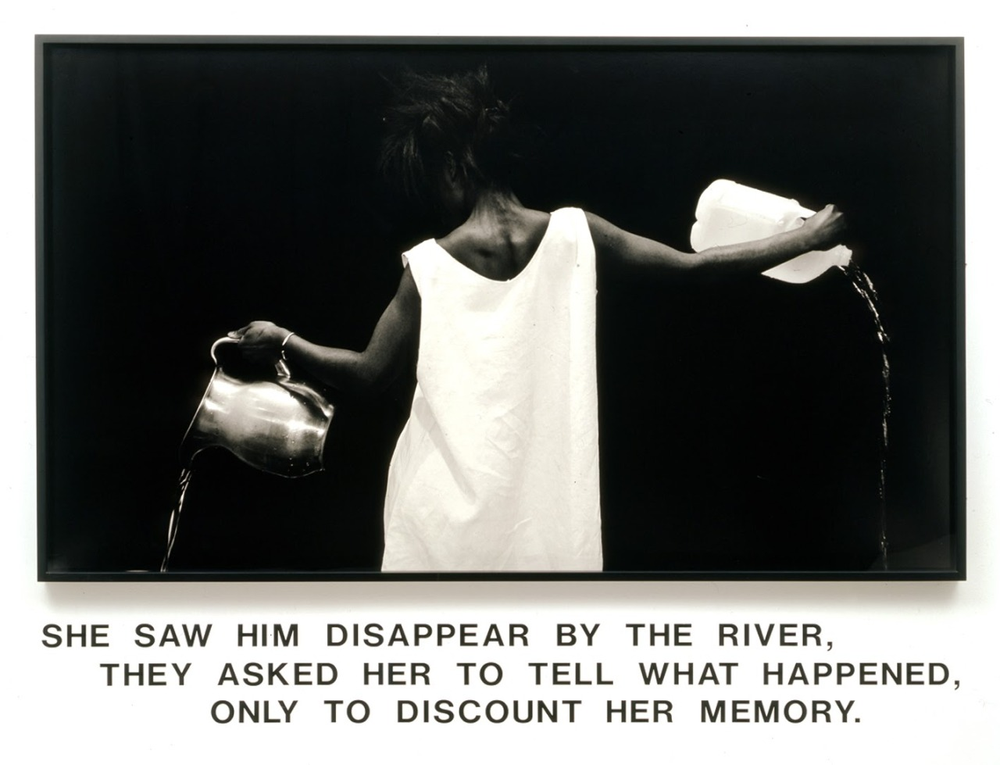

Lorna Simpson embodies a resistance to violent language and meanings, and a kind of “feminine écriture” in her early photographic work Waterbearer (1986). Simpson elaborates on her use of text in conjunction with the powerful photographic image, saying: “…in the conveyance of memories, I noticed there was a lot of stopping short, or a tendency not to fill in all the blanks. There also was the consideration that memory is a contentious situation in a way, so that what one wants to voice in terms of memory doesn’t always get acknowledged.”[2] The gendered language of the work points to the bias of those whose memories, accounts, and stories are acknowledged. That is, men’s accounts are held up as the truth, while women’s stories are discounted and gradually disappear. This is particularly poignant in stories of sexual abuse, trauma and rape, where there is widespread dismissal of victims’ claims of perpetration by men against women. Simpson’s work also implicates race as a compounding factor of prejudice. Not only are women’s stories and memories categorically invalidated and dismissed as unimportant, even false. Black stories, culture, memories, beliefs and customs have been dismissed, even forcibly erased, for centuries. Simpson’s work not only asks the question of who is allowed to speak, but perhaps more importantly, who is allowed to be believed? Belief in words and language is what creates meaning, like a kind of magic. It is the gap between the words, the space between language and image, where meaning lives and takes root.

[1] https://contemporaryartdaily.com/2020/04/anne-lise-coste-at-dortmunder-kunstverein/n[2] https://theconversation.com/making-art-should-be-uncomfortable-a-conversation-with-visual-artist-lorna-simpson-97818

Related Articles

Weekend Viewing: 13-15 January

It's a new year and there is a brand new lineup of shows opening around the world . Here are some of my top picks for exhibitions to check out this weekend, both online and in person. From biennials to blockbusters and everything in between, this short list will...

My Robot Could’ve Made That

There is a well-known book on modern art called “Why Your Five Year Old Could Not Have Done That.” It speaks to the once-common dismissals of abstract and ‘primitive’ styles of art as childish; art that we now prize above any other genre. But perhaps the next...

Just Stop.

Why using art as a vehicle for protest isn't the solution There’s been a lot of art in the news lately, but not necessarily for the right reasons. We’re used to seeing Picasso, Van Gogh and Munch’s names splashed across the pages of newspapers and the internet, but...