Written by Harriet Maher

November 17, 2021

First published in Sleepover Club Initiative’s Edition One, 2016

We live in a world where women’s body hair is almost completely censored in popular media and the images we consume on a daily basis. Women’s hair removal products are advertised prominently, featuring already-hairless bodies and a veritable arsenal of shaving, waxing and epilating tools. A personal favourite is the Schick Hydro Silk TrimStyle TV advert, which features three women trimming their ‘bushes’ – literally small shrubs placed conveniently over their pubic areas – into the shape of love hearts. Despite this obsession with women’s hairlessness and the media’s refusal to depict women with any body hair below the eyebrows, many feminist artists involve subversive depictions of hair in their work. Hair has been approached politically by feminists for decades, and especially since the early 1970s, when women went unshaved to protest patriarchal standards of beauty for women, and the normative ideal that hairless = feminine. The construction of femininity is exemplary of cultural control over perceived gender norms. Hair removal, or growth, for both cis and trans people is an action both political and personal. There are various arguments against the shaving of women’s body hair, (particularly pubic hair) ranging from the fact that it sexualises girlhood instead of womanhood, and makes women appear more sexless and infantile, thus diminishing their power; to the simple argument that women may choose to do whatever they please with their own bodies and the hair which naturally grows on them. In the four and a half decades since these issues were raised by feminists, the perceptions, public censorship and attitudes surrounding women’s body hair have gone largely unchanged, meaning that female hair is still significant as a feminist issue, and thus is still significant for feminist art. A number of women artists have incorporated body hair into their work to critique its still-controversial nature, and many feminists now proudly show their armpit, facial, pubic and other body hair in their art, on social media and in their daily lives. The continuing importance of this display is evident in the fact that, even in advertisements for products meant to eradicate, or at least minimise, body hair, there is not a single hair in sight.

Hannah Raisin, Flowing Locks. 2007, Performance, Single Channel Video, Photography

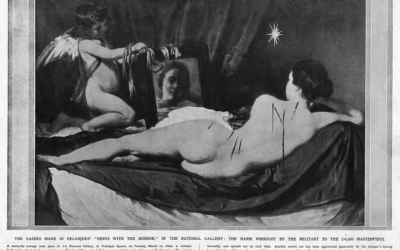

Women’s body hair has been censored not only since the 1970s, but for centuries, both in popular culture and in ‘high art’. Even the women in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel are all completely hairless below the neck, and the female nude, one of the most prominent and long-standing traditions in Western art, is more often than not hairless from the neck down. In more recent art practices and histories, this has been challenged, with many artists focusing on female body hair in their work and challenging the strong taboo around this subject. Contemporary feminist artists have continued to address this controversial subject in their practice, including Melbourne-based performance artist Hannah Raisin. Her 2007 work, Flowing Locks, involves the artist standing outside the striking architecture of the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne, wearing a nude lycra body suit with holes cut in the armpits and pubic area. Attached to these areas are long hair extensions, which flutter around the artist’s body and into the space surrounding her as she dances gracefully, proudly showing off her ‘flowing locks.’ This performance work subverts the usual depiction of female bodies, by covering those areas of skin usually exposed – the arms, legs and torso – and displaying those areas usually covered – the armpits and pubic area. Raisin challenges negative perceptions of body hair and depicts it as something beautiful, graceful and feminine, something to be celebrated and displayed proudly. The exaggerated length of the hair extensions also brings an element of comedy to this work, as the audience is at first startled, and then perhaps amused by the amount of hair attached to the artist’s body. Humour is an important tool for feminist artists, as it allows them to convey an important message without being didactic, and also undermines the common assumption that feminists have “no sense of humour.” Curator Laura Castagnini has described Raisin’s performance as “simultaneously a celebration of the natural female body, an ‘up yours’ to contemporary ideals of female hairlessness, and a nod (or a wink?) to feminists of the 1970s.”[1] This seemingly simple performance, of a female performer sporting long body hair, is deeply entwined within the rich and complex history of feminist art which address the taboo around women’s body hair, including seminal artists such as Catherine Opie, Della Grace, Zoe Leonard and Jill Orr.

Deborah Kelly, Beastliness. 2011, single channel digital video animation, colour, sound

Another contemporary artist who has incorporated women’s body hair into her practice is Deborah Kelly, who has explored the transgression of patriarchal standards of beauty through body hair in a number of works. Her 2008-2010 animation Beastliness, for instance, opens with an image of a woman’s face, heavily made up, with a head of thick red hair. Soon, the hair begins to sprout on her face until all we can see are her bright yellow eyes and mouth. The woman becomes ‘beastly’ through the appearance of hair in a place we would not usually expect to see it – at least on a woman. Kelly’s work undermines gender binaries and challenges the discrete body, as facial hair is typically something we, particularly in ‘Western’ societies, are conditioned to read as masculine. Typically, male body hair (particularly facial hair) has been linked to power, strength, fertility, leadership, lustfulness, and masculinity, while female body hair is traditionally associated with insanity, witchcraft and the devil.

Themes of female beastliness and body hair recur in Kelly’s Hairpiece series (2008-2010). This series features more hirsute women, their beautiful and heavily made-up eyes and mouths strikingly visible amongst thick locks of hair. Once again, Kelly critiques feminine standards of beauty and the perception of women’s body hair as shameful and unclean, instead presenting it in a celebratory manner, rather like Hannah Raisin in Flowing Locks. In The Magdalenes (Penitence), we are presented with a female model with luscious hair covering her entire body, except for her breasts and hands. This bold image calls attention to the invisibility of women’s body hair in the magazines which, ironically, provided the source material for Kelly’s collages. Kelly’s work makes women’s body hair hyper-visible, unavoidable, and perhaps most importantly, alluringly and frighteningly beautiful. These collages are reminiscent of Dadaist works in their surrealism, and remain just shy of being read completely seriously, as the works’ subversion of viewer’s expectations produces ironic laughter. As Emilia Salgado writes, “I can’t help view Kelly’s work and laugh; it is both uncannily true and yet somehow repulsive to be unveiled so.”[2]

Zackary Drucker, The Inability to be Looked at and the Horror of Nothing to See. 2009-10, performance

The discussion of body hair in feminist art is often limited to cisgender women – women who were assigned a female gender at birth and who continue to identify with this gender in adulthood. Hair signifies constructs of our identity, however, and is therefore of significant interest in the work of many transgender artists, who explore the fluidity of sex, gender and bodies in their work. Zackary Drucker, a trans woman artist, has engaged her body in performances that explore hair and hairlessness as part of the transgender experience. In The Inability to Be Looked at and the Horror of Nothing to See (2008-2009), participants were directed through a series of breathing exercises by a disembodied voice, accompanied by new-age philosophies and dark wisdom, as part of a ‘group meditation.’ While doing so, they were also instructed to pluck out the hair from an androgynous, stripped body in the centre of the gallery. The disembodied voice continued to speak as participants used tweezers to extract hair from the chest and leg area of the artist’s body. The hair was given negative connotations, as the voice says: “Imagine that you are uprooting all of the ugly things that are growing inside of you. All your perverse thoughts, your predatory instincts and violent fantasies.”[3] This is significant, as it highlights the different way in which trans women perceive body hair as a negative, rather than a positive aspect of the body. While cisgender women may feel that allowing their body hair to grow is empowering and a way of resisting patriarchal standards of beauty, for trans women who want to look more feminine as part of their gender transition, body hair removal can be an essential part of their identity, as seen in Drucker’s personal, confronting and thought-provoking performance.

Petra Collins, The Hairless Norm no. 16 (detail). 2014, photograph

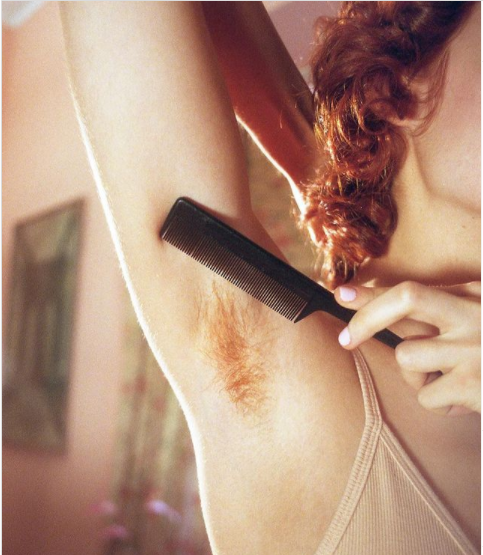

More recently, young feminist artists have faced censorship of their work which depicts women’s body hair and other ‘taboo’ aspects of the female body on Instagram. While images of (body hair-free) models in swimsuits and underwear abound on the social media site, artists such as Petra Collins and Ashley Armitage have had their work censored for its ‘inappropriate’ material. Collins, a feminist artist and writer from Toronto, had her entire Instagram account deleted in 2014 for posting an image of herself in bikini briefs with visible pubic hair. She says “I did nothing that violated the terms of use. No nudity, violence, pornography, unlawful, hateful or infringing imagery. What I did have was an image of MY body that didn’t meet society’s standard of ‘femininity’.”[4] Armitage, a Seattle-based photographer, captures her friends and acquaintances in a candid, personal manner as “an exploration of what it means to represent femininity through a woman’s viewpoint and not through a man’s fantasy.”[5] Her photographs are intimate snapshots of uncensored teenage femininity, including armpit, leg, facial and pubic hair, cellulite, and stretch marks, celebrating the female body in its ‘natural’ state. In particular, one photograph shows a close-up of a woman in blue bikini briefs, which appear as though they have been stained with period blood, and whose pubic hair is visible beneath the fabric. Armitage says she received a lot of negative feedback for this image, despite the fact that it depicts no nudity or obscenity, and it was removed from Instagram. After re-posting the image, Armitage wrote “The censorship of a photo that shows a natural bikini line is like saying a woman’s natural body is obscene, abnormal, and unacceptable. It’s like saying that in order to be decent and acceptable, we must shave to fit the beauty standard.” Armitage confronts patriarchal standards of beauty by showing the beautiful side of what are usually considered ‘flaws’ in femininity: belly rolls, stretch marks, body hair and period blood.

Ashley Armitage, Instagram post August 4 2018. Photograph.

The insistence of young feminist artists on showing body hair in their work as natural and beautiful is crucial for challenging patriarchal standards of beauty which are still rigidly enforced by sites like Instagram, which promote photos of hairless models photoshopped to within an inch of their lives, but remove photos of the natural state of the female body such as in Petra Collins’ and Ashley Armitage’s photos. Trans people are importantly navigating a different position towards body hair, sometimes embracing it and sometimes choosing to have it removed to assert a feminine identity. The continuance of patriarchal standards still enforced on women’s bodies and the censorship of feminist art portraying body hair is evidence of the enduring significance of body hair in feminist art. Barbara Kruger’s 1989 statement “Your body is a battleground” still rings true for feminist artists today.

[1] Laura Castagnini, ‘Backflip: Feminism and Humour in Contemporary Art’, NAVA Quarterly: Women in Art. http://lauracastagnini.com/project/backflip-feminism-and-humour-in-contemporary-art/. Accessed 7/12/15[2] Emilia Salgado, ‘Deborah Kelly’ 22/9/11, http://artoutwrite.blogspot.com.au/2011/09/deborah-kelly.html, accessed 9/12/15[3] Zackary Drucker, The Inability to Be Looked at and the Horror of Nothing to See’, http://zackarydrucker.com/performance/the-inability-to-be-looked-at-and-the-horror-of-nothing-to-see/, accessed 4/1/16[4] Petra Collins, “Why Instagram Censored My Body”, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/petra-collins/why-instagram-censored-my-body_b_4118416.html?ir=Australia, accessed 4/1/16[5] Armitage quoted in Erica Tempesta, ‘Photographer celebrates the natural female form by posting images of women’s pubic hair and fat rolls on Instagram in order to challenge what it means to be ‘feminine’’, Daily Mail 18/11/15. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-3324036/Photographer-celebrates-natural-female-form-posting-images-women-s-pubic-hair-fat-rolls-Instagram-order-challenge-means-feminine.html, accessed 25/11/15

Related Articles

Weekend Viewing: 13-15 January

It's a new year and there is a brand new lineup of shows opening around the world . Here are some of my top picks for exhibitions to check out this weekend, both online and in person. From biennials to blockbusters and everything in between, this short list will...

My Robot Could’ve Made That

There is a well-known book on modern art called “Why Your Five Year Old Could Not Have Done That.” It speaks to the once-common dismissals of abstract and ‘primitive’ styles of art as childish; art that we now prize above any other genre. But perhaps the next...

Just Stop.

Why using art as a vehicle for protest isn't the solution There’s been a lot of art in the news lately, but not necessarily for the right reasons. We’re used to seeing Picasso, Van Gogh and Munch’s names splashed across the pages of newspapers and the internet, but...